Deciphering the Legend of the Birds: history preserved in the oral tradition of the Mackenzies. This article, now lavishly illustrated (mostly with Kevin’s own splendid photographs), is an updated version of Kevin McKenzie’s detective work which was published back in 2018. A new article which builds on this – The Crusader and the Slave – follows

A founding legend which attached itself to Eilean Donan Castle relates that ‘the son of a chief of Kintail acquired the power of communicating with the birds. As a result, and after many adventures overseas, he gained wealth, power, and the respect of King Alexander II, who asked him to build the castle to defend his realm.’ In the Matheson oral tradition, the son’s name is given as Kenneth; he is later equated by the Matheson-descended Mackenzies in their tradition with their late 13th-century forebear Colin.

‘A chief of Kintail reportedly dismissed the lower classes as superstitious fools. To show himself as superior, he set out to prove the ancient legend that said if a child drank its first drink from a skull of a raven, the child would develop powers beyond those of normal humans. From the beginning, the chief’s young son came to understand the language of birds and conversed with them.

The boy’s relationship with his self-imposing father suffered when the child grew into adulthood. The father asked his son what the starlings chattered of outside the chief’s window. However, when the young man said the starlings spoke of a day when the chief would wait upon the son, the vain chief drove his son from the family lands.

The chief’s son eventually arrived in France. The King’s peace had been greatly disturbed by a flock of sparrows. The young man offered his services to the King. The man discovered there was a feud between several species. He negotiated a peace, which silenced the angry screeching the King had experienced and replaced the screeches with melodic chirruping. The King gave the young man a ship and crew.

The young man continued his journeys and was rewarded time and time again for his ability to speak to the birds. He collected gifts most wondrous. Finally, the young man arrives in a kingdom plagued by rats. The birds could not solve the kingdom’s problems, but a gift of a cat set the palace aright. The king rewarded the young man with a casket of gold.’

We may conclude the story with the ending to the Mackenzie version of the legend as given by Rorie, late Earl of Cromartie, in his erudite book, A Highland History (first published in 1979, and which was very much instrumental in sparking off my interest in the Mackenzies’ family history):

‘After a lapse of ten years he returned home and moored his splendid galley between Totaig and Eilean Donan; his father thinking his visitor to be, if not a king, some puissant prince, entertained him royally, serving with his own hand the wine to his guest; in this manner was the prophecy of the starlings fulfilled. When Colin made known his identity, his father, at first, could not believe that this rich and experienced man of the world was truly his son, but was eventually convinced by the sight of a birthmark on the youth’s shoulder.’

And in another version of the story:

‘The chief’s son had learned much in his travels. He could speak different languages and knew the intricacies of foreign cultures. He was recognized as a great man by one and all. As such, King Alexander gave the chief’s son the honour of being the one to oversee the building of Eilean Donan’s castle, a castle to defend Kintail lands beyond from Norse attack.’

The legend has much in common with the story of Dick Whittington and his cat. A similar founding legend attached itself to Dundonald Castle. Indeed: ‘Similar legends can be found throughout Europe and the Middle-East. The earliest version is one of the poems of the Mathnawi, entitled In Baghdad, Dreaming of Cairo: In Cairo, Dreaming of Baghdad, by 13th-century Persian poet Jalal al-Din Rumi; This poem was turned into a story in the tale from The One Thousand and One Nights: The man who became rich through a dream; and spread through various countries folklore, children’s tales and literature. More recently the story was adapted into the plot of the novel The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho’. But in fact the 10th-century Persian story of Keis(h) travelling to India with his cat and being rewarded by the King for ridding his palace of a plague of rats is the earliest. Sir William Ouseley discovered this story during his eastern travels and published it in 1819.

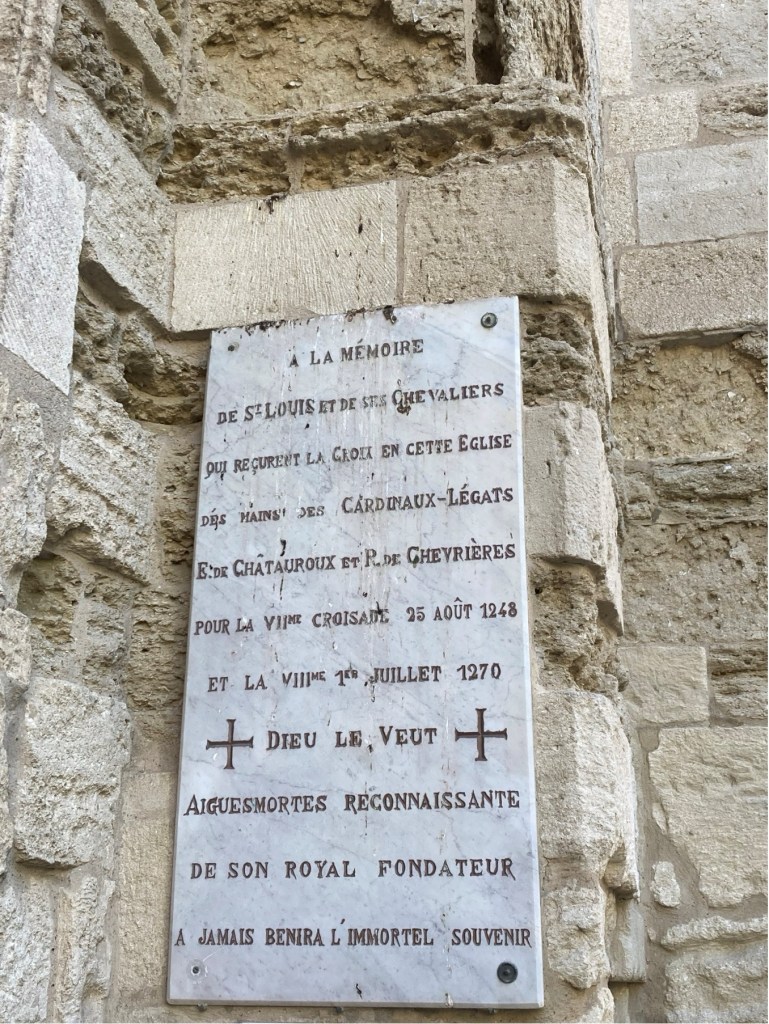

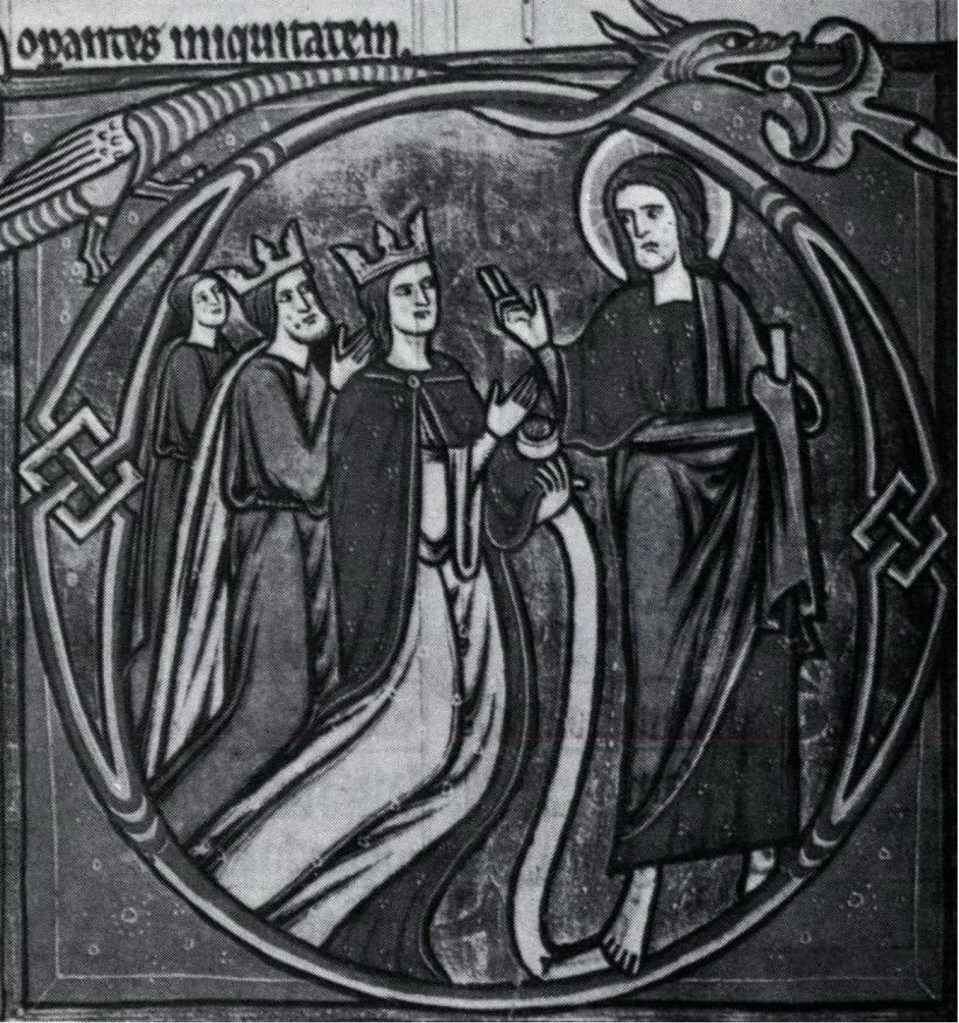

Matthew Paris’s mid-14th-century Chronica majora records that in preparation for the Seventh Crusade Hugh (V) de Chatillon, Count of St Pol and Blois, built a wonderful ship (‘navis miranda’) in Inverness which was used to transport himself, his followers and their horses to Flanders with a view to their joining the forces of the French King Louis IX in the Holy Land. (The Master of the Templars in Scotland was present at the crusaders’ defeat in Egypt in 1249, and communicated news of the disaster to Matthew Paris at St Albans; he was most probably the source of this information). Aside from the fact of his visiting distant lands and being in the company of the King of France, from the evidence of his having by 1262 become a notable warrior and my own new genealogical findings, with which I conclude, it is highly likely that Kenneth was part of this particular crusading company.

‘The good Comte’ Hugh (who we know from Joinville was close to King Louis – he is recorded as waiting on the Queen at a great feast held by the King at the Chateau de Saumur in 1241) then travelled overland and died very early in the Crusade, killed in a skirmish when passing near Avignon in April 1248. The surviving men then dispersed and most of the 50 knights returned home. The founding legend certainly indicates, however, that Kenneth must have eventually met up with Louis. We can surmise, therefore, that he must have gone on to one of the crusaders’ departure ports, most likely nearby Marseille, and that he most probably sailed from there with Hugh’s nephew Gautier (Walter) de Chatillon, and the latter’s brother-in-law (the Lord of Bourbon) and cousin (Gautier de Chatillon-Autreche).

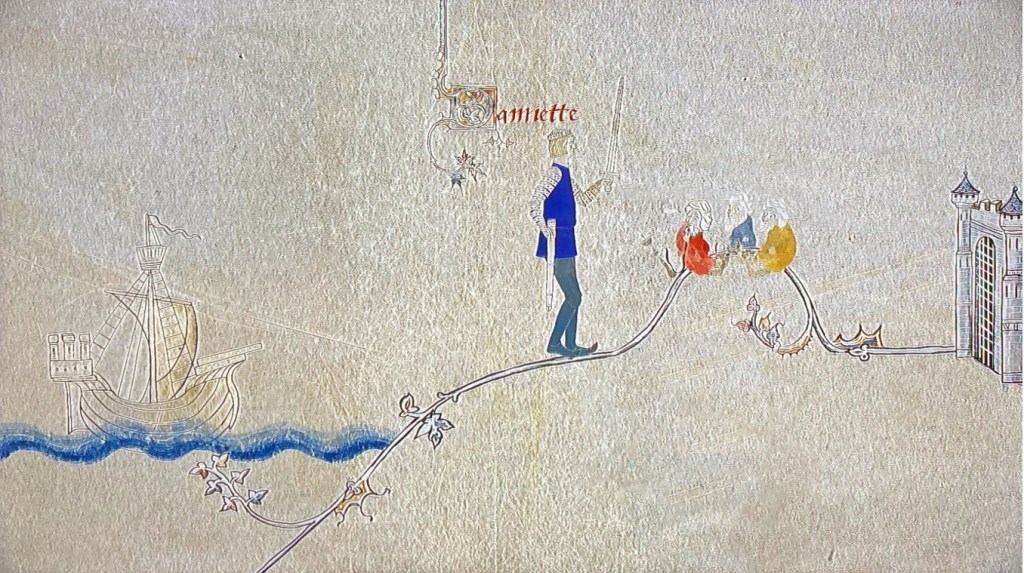

For we know that Hugh’s nephew Gautier wintered in Cyprus in 1249 (where Bourbon died) and ‘bore himself gallantly oversea, and would have proved his worth still more if he had lived longer’. As Jean de Joinville goes on to record in his first-hand account, in 1249 they arrived from Cyprus at Damietta in Egypt, where they found ‘the full array of the sultan’s forces drawn up along the shore. It was a sight to enchant the eye, for the sultan’s arms were all of gold, and where the sun caught them they shone resplendent. The din this army made with its kettledrums and Saracen horns was terrifying to hear’. In February 1250, in a major battle at Al Mansourah nearby, ‘the king sent us Gautier de Chatillon, who took up his position in front of us, between the Turks and ourselves.’ The next day it seems, Gautier’s battalion, ‘containing a full complement of gallant men, all noted for their knightly deeds … defended themselves so vigorously that the Turks were never able to pierce their ranks or oblige them to fall back’. The next to meet the enemy’s onslaught was the Master of the Temple, who lost an eye. The forces of the new Egyptian sultan, Turanshah, used Greek fire (‘like a great hedge of flame’, it ‘seemed like a dragon flying through the air’ – it was ‘so bright that you could see through the camp as clearly as if it were day’ and the arrows tipped with it ‘seemed like the stars falling from heaven’), destroying many of the crusaders’ vessels.

Later in the engagement, Joinville records that when the Egyptians attacked King Louis’s camp, Louis had ‘gladly’ granted Gautier’s request to form the rear-guard of the King’s personal forces there. Indeed, we know that Gautier like his uncle was close to Louis: he was married to the King’s first cousin, Johanna of Clermont. ‘My knights joined me, all wounded as they were; and we drove the Saracen Serjeants out from among the engines, and back onto a large squadron of mounted Turks, who were close to the engines we had captured. I sent to the King asking for help, for neither I nor my knights were able to put on hauberks, because of the wounds we had received; and the King sent us my Lord Walter of Chatillon, who placed himself in front, between us and the Turks. When the Lord of Chatillon had repulsed the Saracen foot-serjeants, they fell back on a large squadron of Turks on horseback who were drawn up in front of our camp, to prevent us surprising the Saracen camp, which lay behind them.’

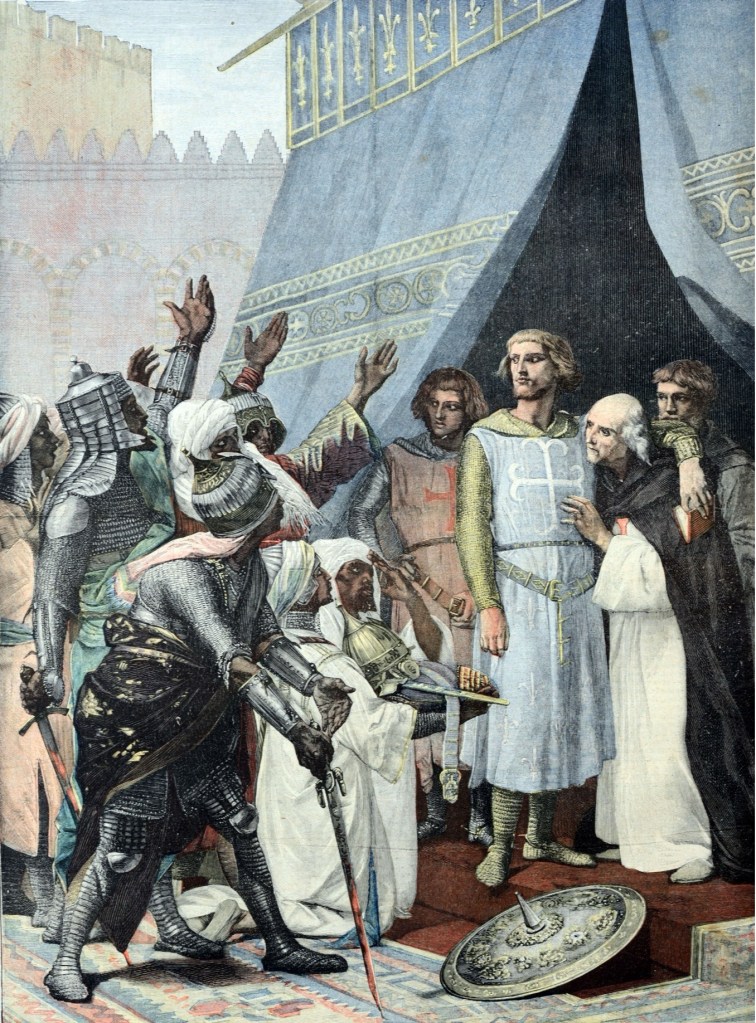

A few months after Al Mansourah, King Louis’s army was annihilated – some crusaders even deserted to the Moslem side – at the Battle of Fariskur (April, 1250). The King recounted to Joinville how he and a few of his nobles who survived were captured in a village nearby, and he was imprisoned in the house of the royal chancellor, under the guard of a eunuch. The 13th-century personal toilet which Louis used still survives there. He fell ill with dysentery, was cured by an Arab physician and, just as in the founding legend, a peace was negotiated: Louis’s life was spared and he and 12,000 prisoners, which must have included Kenneth, were freed on payment of a ransom of 200,000 livres. The King and his fellow crusaders then left for the French garrison camp of Acre (the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem). During his captivity, Louis’s queen, who was at Damietta, had nightmares that her room was full of Saracens and ran around screaming for help. She gave birth there to a son named Jean Tristan (‘sorrow’). At the village near Fariskur, Gautier had held up the enemy until his fellow rear-guard commander Geoffroy de Sargines (charging at the Saracens with his spear and driving them away from the King) could bring Louis, who was ‘mounted on a cob with a housing of silk’, to safety in a hut where he eventually surrendered and was taken into captivity:

‘I must not forget certain matters that occurred in Egypt whilst we were there. First of all I will tell you about my Lord Walter of Chatillon: how a knight named Lord John of Monson, told me that he saw my lord of Chatillon in the walled village where the King was taken. A street ran straight through the village, so that one could see the fields on either side. In this street was my Lord Walter of Chatillon with his naked sword in his hand. As often as he saw the Turks entering this street, he charged upon them, sword in hand, and hustled them out of the place; and whilst the Turks were fleeing before him, they (who shoot as well backwards as forwards) would cover him with darts. When he had driven them out of the village, he would pick out the darts that were sticking all over him; and put on his coat-of-arms again; stand up in his stirrups, and brandishing his sword at arm’s length cry, “Chatillon! Knights! Where are my paladins?’. Then, turning round, and seeing that the Turks had come in at the other end of the street, he would charge them again, sword in hand, and drive them out. And this he did about three times in the manner I have described.

After the Emir of the Galleys had brought me to those who were captured on land, I made inquiries of such as belonged to Lord Walter’s household, but I never found anyone who could tell me how he was taken. Only Lord John Frumons, that good knight, told me that, when they were leading him away prisoner to Mansoora, he met a Turk who was riding Lord Walter of Chatillon’s horse, and the horse’s crupper was all bloody. And he asked the Turk what he had done with him whose horse it was; and the Turk answered, that he had cut his throat on horseback, as might be seen from the crupper that was all covered with the blood.’

Shortly after Fariskur, Sultan Turanshah also met with a bloody end – having escaped, following a great banquet, from a rival Mamluk faction to a tower near the River Nile, this was set on fire. He waded out into the river, where he was shot with arrows and, whilst begging for his life, hacked to death. His heart was cut out by his Mamluk assassin who presented it to the captive King Louis, hoping to receive a reward. ‘But the king did not answer him a word’.

It is more than possible that the story of Keis had been transmitted to Damietta via Rumi to his fellow Sufis at the court of al-Kamil, the Sultan of Egypt, who was a nephew of Saladin, and was later re-told by Kenneth, as a returned crusader knight, as a fireside tale of exotic and faraway realms to entertain the household within the cold walls of Eilean Donan. There a memory of the story must have survived, mingled with the life story of Kenneth himself (transposed to become the hero of the story) and (as we shall see) his son John. What seems to me to lend further support to this is the fact that in the legend Kenneth, like St Francis of Assisi, is said to have learnt the language of and spoken to the birds. Francis had met with the Sultan al-Kamil in Damietta, a number of noteable Sufi influences can be seen in his personal theology and, like King Louis of France (who is believed to have been a member of the Third Franciscan Order) and his crusaders, on leaving Damietta had departed for the camp at Acre, which was plagued by rats.

Not only do we have the link with the region of Scotland provided by Matthew Paris’s chronicle, but MS 1467 identifies the mutual Matheson and Mackenzie forebear who was living around the time the family line first acquired Eilean Donan as Kenneth Macmathan (Gaelic: Coinneach Mac Mathghamhna – i.e. son of Mathan (‘the bear’) – the latter being the nickname of a man whom I have identified as appearing in the early genealogies as Angus Crom (‘humpbacked’, just like a bear)). So, as William Matheson, the scholar of Gaelic Scottish poetry and Highland history noted, the young man who is the subject of this shared clan oral tradition is clearly Kenneth, the Mackenzies’ and the Mathesons’ shared chiefly forebear of this period.

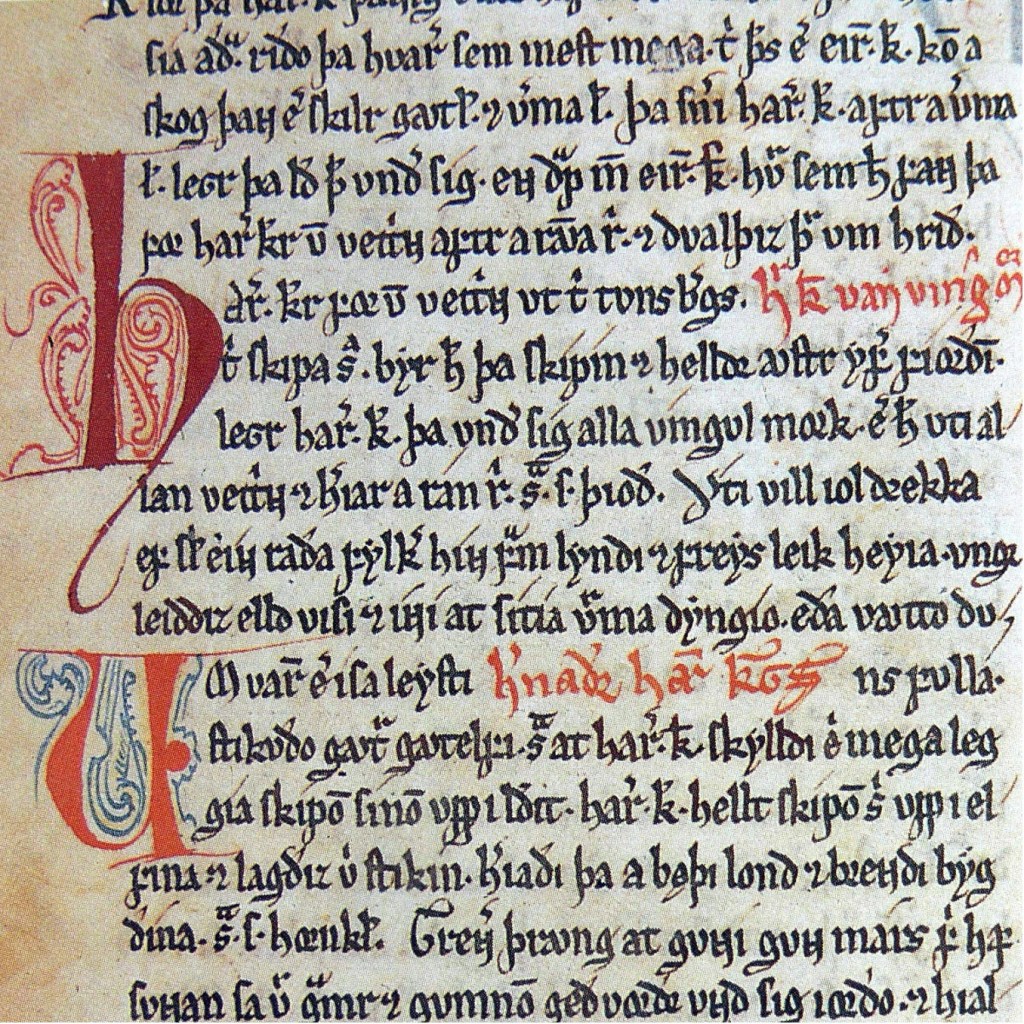

That Kenneth was a notable warrior is also confirmed by an old Norse saga the Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, a copy of which survives as part of the early 14th-century Codex Frisianus, in which his name is given in Old Norse as ‘Kiarnakr’, or Kennac, ‘f. [son] Makamal[s]’. The events narrated took place in 1262/3, at the time of the Hebridean conflict between Kings Haakon (Haco) IV of Norway and Alexander III of Scots. The story of Haakon’s birth and ascension to the throne have recently been dramatised in the acclaimed Norwegian film The Last King (2016). He has himself also become an ancestor of many members of the clan by virtue of Mackenzie marriages in the late 15th and early 16th Centuries with the Frasers of Lovat, who descended in the female line from Haakon through the heiress Isabella of Caithness.

Whether these atrocities actually took place (they are a common enough story), and if so whether Kenneth was personally responsible for any of them, we shall most likely never know, but his crusading experiences as a young man had evidently turned him into a hardened warrior:

‘MCCLXII

In summer there came letters from the Kings of the Hebrides in the western seas. They complain’d much of the hostilities which the Earl of Ross, Kiarnach, the son of Mac-camal, and other Scots committed in the Hebrides when they went out to Sky [sic]. They burned villages, and churches, and they killed great numbers both of men and women. They affirmed that the Scotch had even taken the small children and raising them on the points of their spears shook them till they fell down to their hands, when they threw them away lifeless on the ground.

They said also, that the Scottish King purposed to subdue all the Hebrides, if life was granted him.

When King Haco heard these tidings they gave him much uneasiness, and he laid the case before his council. Whatever objections were made, the resolution was then taken, that King Haco should in winter, about Christmas, issue an edict through all Norway, and order out both what troops and provisions he thought his dominions could possibly supply for an expedition. He commanded all his forces to meet him at Bergen, about the beginning of spring.’

Haakon then set out for the Hebrides to revenge the devastation on Skye. As the saga goes on to record:

‘During this voyage King Haco had that great vessel which he had caused to be constructed at Bergen. It was built entirely of oak, and contained twenty-seven banks of oars. It was ornamented with heads and necks of dragons beautifully overlaid with gold. He had also many other well-appointed ships.’

‘No terrifier of dragons, guardians of the hoarded treasure, e’er in one place beheld more numerous hosts. The stainer of the sea-fowl’s beak, resolved to scour the main, far distant shores connected by swift fleets.

A glare of light blazed from the powerful, far-famed monarch while, carried by the sea-borne wooden coursers of Gestils, he broke to the roaring waves. The swelling sails, of keels that ride the surge, reflected the beams of the unsullied sun around the umpire of wars.’

Haakon’s fleet encountered a storm and ran aground. So great was the tempest that it was believed to have been raised by the power of Magic:

‘Now our deep-enquiring Sovereign encounter’d the horrid powers of enchantment, and the abominations of an impious race. The troubled flood tore many fair gallies from their moorings and swept them anchorless before its waves.

A magic-raised watery tempest blew upon our warriors, ambitious of conquest, and against the floating habitations of the brave. The roaring billows and stormy blast threw shielded companies of our adventurous nation on the Scottish strand.’

Their having run aground off the Scottish coast, the Scots now advanced against the Norwegian vessels, and their army was conjectured to consist of near 1,500 knights. ‘All their horses had breast-plates; and there were many Spanish steeds in complete armour.’

Kenneth must have fought with King Alexander III against Haakon at this famous battle, Largs, in October 1263, as he is recorded as ‘Kermac Macmaghan’ in a surviving 17th-century transcription of the contemporary Chamberlain’s Rolls as receiving compensation from the King for his services that year. A witness to this was ‘Alan Hostarius’ whose father Thomas de Lundin, sheriff of Inverness, was a witness to the ‘fabricated’ 1266 charter to Kenneth’s son John’s likely Fitzgerald father-in-law ‘Colinum Hybernum’ (aka Sir Gilmore Macgylecho) of the lands of Kintail (which was in fact dated 1270, and the genuine existence of which my brother Andrew and I support with our analysis in Appendix A of May we be Britons?).

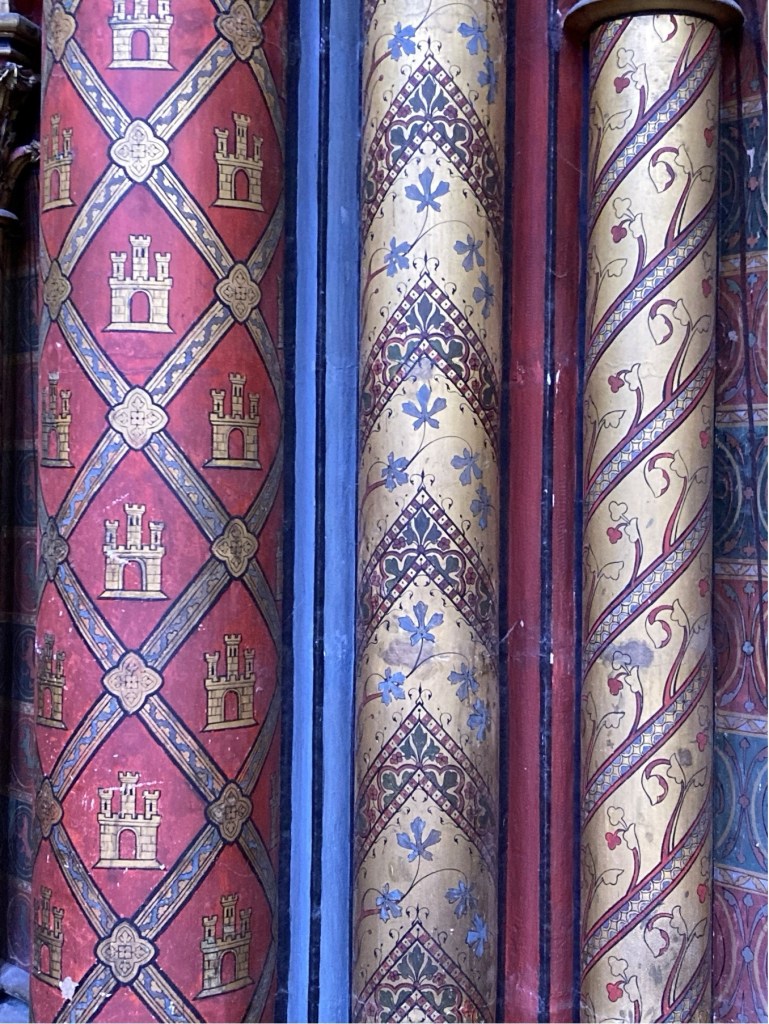

The early clan histories confirm that one of the early chiefs of Kintail married the ‘sister’ of William I Earl of Ross (with whom, as the Codex Frisianus confirms, Kenneth devastated Skye, then fought against Haakon IV). My own recent research now indicates that this ‘sister’ was in fact the Earl’s sister-in-law, who was a Comyn, that her nephew John I Comyn the Red was in 1240 Alexander II’s ambassador to Louis IX, and most significantly of all that the Comyn family was immediately descended, through one Sarah Fitzhugh, from Hugh III Campdeveine, Count of St Pol. The Comyns bore the same emblem (azure three garbs or) as this family of crusader counts, and Sarah Fitzhugh was born in Moray-shire where, along with Inverness (where they built their ship) the St Pols (with their base at St Pol in Flanders) had settled and had followers. The silver star which used to appear between the deer’s antlers in the earliest versions of the Mackenzies’ chiefly coat of arms is said to have been a Moray star and the other families who bore this device are said to have had a Flemish origin. The chronology makes clear that it would have been Kenneth’s father Mathan who would have married this Comyn ‘sister’ of the Earl of Ross, and who was descended from the St Pols, in around 1220 to 1230.

And the young Kenneth’s cousinship with the St Pol family would not only now explain his embarking in 1248 on the Seventh Crusade (as part of Gautier de Chatillon’s rear-guard contingent, whereby he would have been in the company of King Louis IX), but also the existence in the chiefly arms of the Carolingian device of the silver star. This charge also appears in versions of the Comyn family’s arms. For, significantly, these relationships would in turn have meant that the early Matheson/Mackenzie chiefs were descended from Hugh III’s countess, who was an heiress of Adelaide of Vermandois, the last of the Carolingians. My brother Andrew and I have already shown how Kenneth’s son John Macmathan used for his seal exactly the device of the eight-petalled flower as his cousin John III Comyn the Red in the 1296 Ragman Roll; and that John is likely to have married the daughter of the Fitzgerald and Macleod family member Sir Gilmore Macgylecho, who affixed his seal in the company of the same John III and whom we can identify as ‘Colinum Hybernum’, the holder of Eilean Donan Castle and apparent originator of the stag’s head arms. John most likely thereby acquired possession of the castle. Part of this heraldic detective work involved using the clue provided by another legend of the Mackenzie oral tradition, the Legend of Loch Maree, with its story of the Son of the Goat. Hence the stories associated with the father (Kenneth) would also have become associated with the son (John) (for whom the latter’s father-in-law, ‘Colin’, is then transposed), whereby they became part of the castle’s founding legend.

All of this fits very neatly in a further way. The motto which went with the early version of the Mackenzie chiefly arms with the star was Fide parta, Fide aucta (‘in Faith acquired, in Faith increased’). Kenneth with his Comyn mother and St Pol descent would inevitably have been the first in the Mackenzie chiefly line to have borne the Carolingian star. And he did so fighting as a Crusader. So the wording of the motto makes perfect sense. I would also suggest that because of all of this, and his prominence in the family line both militarily and heraldically, Kenneth Macmathan was the original Kenneth after whom the Mackenzies named themselves.

I spoke recently to a German academic historian with expertise on the oral tradition of the Inuit, in connection with Sir John Franklin’s expedition to the Arctic. His own studies had shown that cultures which do not depend on written records have a far more accurate transmission of oral knowledge than those who do, as it is most often the memory of reading written records which clouds the memory of oral story-telling and subsequent transmissions. Altered in its transmission as it clearly has been, and confused as it clearly became with stories from the same time-frame, Eilean Donan Castle’s founding legend is a remarkable survivor: it was far from being simply fabricated and both it and these 13th-century sources can be presented (to such doubters as may still exist) as strong corroboration of much of the disputed genealogical information contained in MS 1467 and, more recently, the clan history of the 1st Earl of Cromartie. Sadly, the latter is a demonstrably largely correct genealogy, but one which it has been the much-parroted received wisdom to accuse the Earl of ‘falsifying’.

Kevin McKenzie

Regent’s Park, December 2017 (article updated August 2025).

© Kevin McKenzie, 2025