Benjamin West’s Alexander III of Scotland Rescued from the Fury of a Stag by the Intrepidity of Colin Fitzgerald

INTRODUCTION BY ANDREW MCKENZIE

We are grateful to Professor Hugh Cheape of Sabhal Mòr Ostaig (the University of the Highlands and Islands), for supplying the following essay for the Clan Mackenzie Initiative website. It was very much thanks to Hugh Cheape’s foresight, when he was working for the National Museums of Scotland, that Benjamin West’s Death of a Stag was secured for the Scottish nation in 1987. This was against some resistance at the time, when others regarded the painting as an old-fashioned and anachronistic piece of historical myth. I remember first setting eyes on this painting in 1982 when my brother, Kevin and I picked up the key to what was then called Fortrose Town House and let ourselves in, so that we could view the Seaforth family portraits, which had previously hung at Brahan Castle. Peeping behind a stage curtain, we drew it back to reveal West’s masterpiece. I later learned that local school children used to play badminton up against it, and Michael Gallagher (who conserved it for the National Gallery and is now a chief conservator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York) told me that, when they first took it off the wall, a shower of shuttlecocks poured on to the team from the National Gallery! When I next visited Fortrose in 1986, while researching my undergraduate degree dissertation about the man who commissioned the painting, Francis Humberston Mackenzie, I remember signing a petition to prevent the sale of the painting. At that time it was feared that it would no longer be accessible to the public. Thanks to Hugh, those fears were unfounded. In his words, “Benjamin West’s painting marks a particular moment in time in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century rehabilitation of the Highlander and the transformation of Highland dress from the mark of the rebel into an icon of national identity.” Hugh rightly recognised the important place that even myth has in cultural identity and saw its crucial place in British art history, at a time when Scotland was readjusting its view of its place in the world. It now deservedly hangs opposite Sir Edwin Landseer’s equally monumental “Monarch of the Glen” in Edinburgh’s National Gallery.

THE CHANGING IMAGE OF THE HIGHLANDS AFTER 1745

Hugh Cheape

This text is an expanded version of a paper given at the conference in the National Gallery of Scotland in February 2005 marking the completion of the conservation of Benjamin West’s massive masterpiece ‘Alexander III of Scotland rescued from the fury of a Stag’.

Introduction

‘I see into the far future, and I read the doom of the race of my oppressor. The long-descended line of Seaforth will, ere many generations have passed, end in extinction and in sorrow. I see a chief, the last of his house, both deaf and dumb. He will be the father of four fair sons, all of whom he will follow to the tomb. He will live careworn and die mourning, knowing that the honours of his line are to be extinguished for ever, and that no future chief of the Mackenzies shall bear rule at Brahan or in Kintail. …. The remnant of his possessions shall be inherited by a white-hooded lassie from the East, and she is to kill her sister. And as a sign by which it may be known that these things are coming to pass, there shall be four great lairds in the days of the last deaf and dumb Seaforth … of whom one shall be buck-toothed, another hare-lipped, another half-witted, and the fourth a stammerer. Chiefs distinguished by these personal marks shall be the allies and neighbours of the last Seaforth; and when he looks around him and sees them, he may know that his sons are doomed to death, that his broad lands shall pass away to the stranger, and that his race shall come to an end.’

According to the nineteenth-century Inverness historian and editor, Alexander Mackenzie – known fondly as ‘Clach’ to his fellow townsfolk – this fearful doom was uttered by Coinneach Odhar, famous to posterity as the ‘Brahan Seer’. Alexander Mackenzie’s intriguing book, The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer, was first published in 1877 and significantly is still in print. It supplies a topical and typical gathering of traditional lore, typical because it is so difficult to measure between history and artifice and because it represents a version of Highland history encoded by a Victorian Highlander. Writing of course for an English-speaking readership, such writers have often done their countrymen and Gaelic posterity no favours. As with Benjamin West’s magnificent canvas however, this is a version of the past and to be judged and enjoyed as such; and it is relevant to give some space to the Brahan Seer because the received narrative and all its byways remind us of the strength and significant elements of clan tradition and the ways in which these were perceived in the eighteenth century and reflected or refracted in the West painting. The painting seems to offer a counter-charm to the bewitching prophecy of the death of the deaf and dumb Cabar Fèidh, and a bid for immortality.

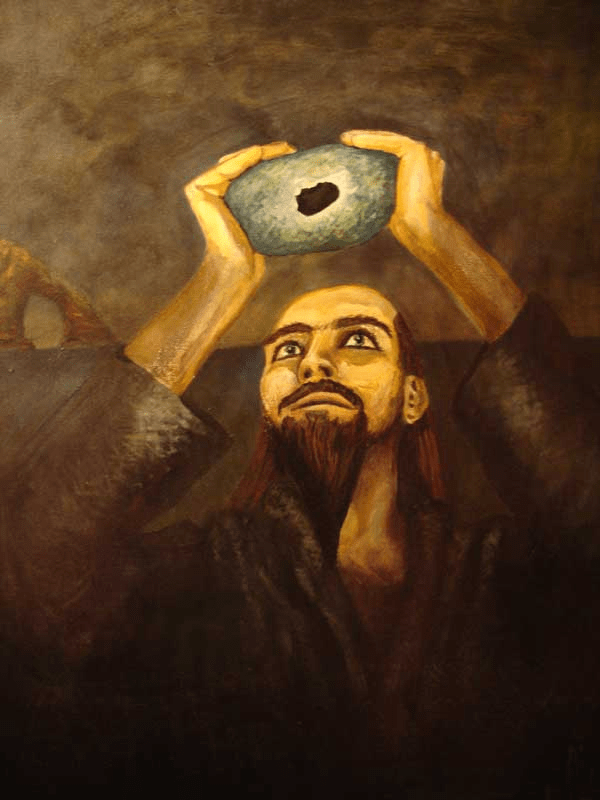

The Mackenzies of Seaforth

According to tradition, the Seer was born and acquired his gift of prophecy or supernatural powers in the Island of Lewis, although, alternatively, Hugh Miller refers to him in his Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland as a ‘Highlander of Ross-shire’ and a field labourer in the vicinity of Brahan Castle. All are agreed that the Seer discovered a stone, beautiful and like a pearl, which conferred a power to see into the future. The proceedings in 1577 for a trial for witchcraft include the name of Coinneach Odhar placing him in the sixteenth rather than seventeenth century. But the story depends on his association with the Earl and Countess of Seaforth, titles which only existed from 1623. The Seer’s quarrel with the Countess of Seaforth and his consequent death at Chanonry Point by Fortrose, burnt in a barrel of tar having been accused of witchcraft as well as prophecy – the victim of spite – is probably not therefore historical fact or is a conflation. His prophecies have naturally caught the imagination and have passed into popular lore, foreseeing inter alia, for example, the Highland Clearances and the construction of the Caledonian Canal. The Brahan Seer legend seems to have a kernel of truth but has recreated itself as an amalgam of several traditions. Hugh Miller recounts the less dramatic prognostication of ‘a deaf Seaforth’, rendering the name in a way which is reconcilable with the earlier title of the Mackenzie chieftain as Gaelic Mac Choinnich.

Francis Humberston Mackenzie, Lord Seaforth, by Sir Henry Raeburn

Francis Humberston Mackenzie, Baron Seaforth and Mackenzie of Kintail, born in 1754, was the great-grandson of Kenneth, the Royalist fourth Earl of Seaforth, and would have become, by inheritance, Earl of Seaforth had it not been for the attainder meted out on William, the fifth Earl – Uilleam Dubh – for his part in the Jacobite rising of 1715. This dynastic catastrophe was retrieved initially by a pardon from George I. It was said that, for many years during this period, the rents of the Mackenzie lands in Kintail and in Lewis were still collected by the factor or chamberlain, Donald Murchison, for the Chief in exile and remitted to him in France, such was the loyalty of his people towards him. This episode, as we know, formed the subject-matter of Landseer’s painting commissioned in 1855, and is also commemorated in ‘Murchison’s Monument’ on the A87 by Kyle of Lochalsh.

Sir Edwin Landseer, Rent Day in the Wilderness

William’s son, Kenneth, was a Member of Parliament and created Lord Fortrose and lived most of his life in London. His clearly Hanoverian stance might help to explain why the fugitive Prince Charles Edward Stewart met with such a cool reception in Lewis following the defeat at Culloden. The next chief, another Kenneth, was also a Member of Parliament and his loyalty to the government allowed him to be able to buy back the clan lands and was rewarded with titles, Baron Ardelve, Viscount Fortrose and finally, in 1771, Earl of Seaforth in the Peerage of Ireland. He offered to raise a regiment from his estates, designated at first the 78th Regiment, later renumbered as the 72nd Regiment. He died on passage to India in 1781.

Francis Humberston Mackenzie was an intelligent and intriguing individual, clearly spending heavily and ambitiously to promote the restitution of his name and family. When he succeeded to the Seaforth estates on the death of his elder brother in 1783, these included the Island of Lewis which had passed under Mackenzie control at the turn of the seventeenth century. This conquest represented one of the most significant achievements in the territorial expansion of the Mackenzies in the North-West Highlands, made at the expense of the MacLeods and ultimately capitalising on the major territorial shifts consequent on the forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles in the late-fifteenth century. Similar opportunities were grasped by the Campbells to the south. Loch Seaforth – Loch Sìthphort or ‘sea-firth’ – the long sea-loch on the east coast of Lewis, gave the Mackenzies the title of their earldom. Better known perhaps for his military and political career, the changes and improvements on his Lewis estates are here as important in any consideration of Francis Humberston Mackenzie as Highland laird, as well as of his view of his own role as chieftain – the paterfamilias of the Gaelic clan. Seaforth was an Enlightenment landlord as with many of his contemporaries, and it was said in Lewis that he was the first of his race to improve the condition of his tenants, his predecessors having looked on the island merely as a source of revenue or manpower. He was involved with schemes to improve the fisheries and his wife taught spinning, knitting and weaving to the island women. Significantly also he tried to reduce the numbers and power of the tacksmen in Lewis (Old Statistical Account Volume 19, 52, 269).

Seaforth and West

Most of this work was still in the future when Mackenzie commissioned the West painting which holds such a remarkable mirror to him. Nearer at hand was the matter of military recruitment and no doubt Mackenzie’s view of his own role as chieftain. He first offered to raise a Highland regiment in 1787 for service in India, but the Seaforth recruits were taken to fill other units. Following the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Francis Humberston Mackenzie of Seaforth offered to raise a Highland Corps on his estates in Ross-shire and in Lewis, to be commanded by himself. The Battalion raised was numbered the 78th Regiment, going into action in the Netherlands in the following year. In the same year a second battalion was raised for the 78th and called the ‘Ross-shire Buffs’. The Colonel was painted in his uniform by the young Thomas Lawrence and the portrait exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1798.

Francis Humberston-Mackenzie, shown in the uniform of the 78th or Seaforth Highlanders

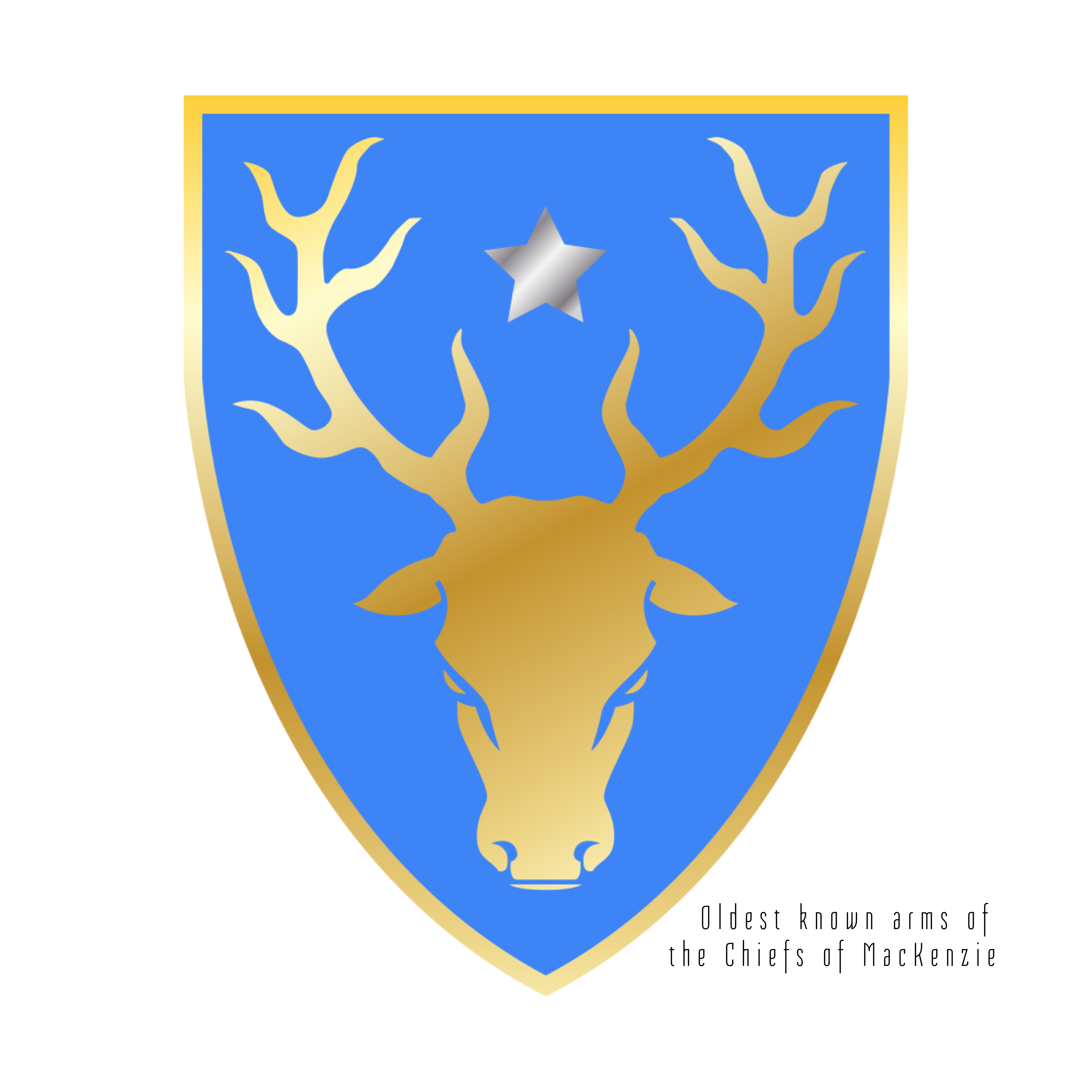

The regimental badge was the stag’s head, the Cabar Fèidh of tradition, and the motto Cuidich an Rìgh (‘Help/Save the King’). The stag figures similarly in the Saint Hubert legend, patron saint of hunters and trappers, who, hunting in the forest on a Good Friday as a young man, was converted to a Christian life by being confronted by a stag with a crucifix between its antlers. The motif is known in other folk-tales, including the foundation legend for the Abbey of Holyrood, telling how David I was about to be gored by a stag but was saved. It appears that a stag’s antlers was one of the crests of the Mackenzies and also a slogan or war-cry – crest and motto apparently being granted by Alexander III to the Seaforth ancestor as the saviour of the king. This is of course the history or tradition so dramatically proclaimed by the West painting. As we now know this was the creation of compilers of family history in the seventeenth century. The tradition of Colin Fitzgerald, the Irish nobleman, was renounced firmly by the historian, William Forbes Skene (1809-1892), in his still important Celtic Scotland (Volume III, 351) published in 1876.

The Legend of St Hubert

What the painting conveys is the importance of traditions, true or false, and the undoubted significance of then placing an Irish ancestor centre-stage. This chimes with the Enlightenment inquiring mind and ‘discovery’ of the past, albeit and not surprisingly a useful and self-serving account of the past designed to promote the position of Seaforth. The centrality of this to the Benjamin West commission tells how important this tradition and the rallying-cry were to the Mackenzie clan in the eighteenth century. A touchstone of clan identity dating from this period is the rousing song Deoch slàinte a’ Chabar Fèidh seo (‘Here’s a health to this Cabar Fèidh’), an outpouring of satire and invective against the Munros and Sutherlands for a cowardly raid of cattle from the Kintail summer shielings. The origin legend is not mentioned though the refrain – ‘When your horn [antler] will be raised on you’ – gives the sense of strength and unity emanating from the ‘Cabar Fèidh’. A further hint of the immediate significance of the ‘Cabar Fèidh’ is offered in a footnote in Sketches of the Character, Manners and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland of 1822 by the soldier-historian, Colonel David Stewart of Garth (1772-1829):

‘It is a curious circumstance that the last Lord Seaforth’s life should have been endangered in the same manner as that in which the first of the family saved the King’s. Lord Seaforth was attacked by a hart in the parks of Brahan Castle; but, being a powerful man, and possessed of great strength of arm, he closed on the animal, and, seizing him by the horns, pressed his breast against the deer’s forehead. A long and desperate struggle ensued, till he was relieved by a gamekeeper who was attracted to the spot by the bellowing of the hart. His Lordship was bruised but not materially injured. The late Mr West painted the rescue of King Alexander. The figures are portraits, in full size, of persons on the Seaforth estate, his Lordship being one of the number. Mr West told me, the last time I saw him, that he considered this painting the best of his earlier pieces.’ (Stewart Sketches, Volume 2, 128)

Eilean Donan Castle in the Death of a Stag painting?

Details in the painting are important for the overall message and set of messages to be conveyed; the castle – we assume Eilean Donan – visible lower left must be noted, but also the hill immediately to its right, the two symbols juxtaposed for recognition. This was probably meant to be Tulach Àrd, the Mackenzie’s gathering place in time of war or on the occasion of assembling in council – in other words ‘High Hillock’. The same phrase was said to be uttered as the Clan war cry. It is still the name of a ‘pibroch’ or extended piece of classical music for the Great Highland Bagpipe. It is included in one of the earliest printed sources of Highland bagpipe music, Angus Mackay’s Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd or Highland Pipe Music, published in Edinburgh in 1838, and also in the manuscript of the Edinburgh bagpipe maker, Donald MacDonald, where the music is also called the ‘Mackenzie’s Gathering’ (see Piobaireachd Society Book 12, 391).

‘This Piobaireachd is very old, but the date of its composition, and its author are unknown. Tulloch ard, or high hillock, was the height on which the beacon was lighted, to warn the country of impending danger, and there burned, while the Croishtaraidh, or fiery cross, was sent through every strath or glen to rouse the inhabitants, who with alacrity obeyed its summons. This hill forms the crest of the family of Seaforth, but is often mistaken for a volcanic mountain, being heraldically termed a mountain inflamed, and is accompanied by the motto Luceo, non uro i.e. ‘I enlighten, I do not burn’. The Mackenzies became very powerful in the north, and had many subordinate tribes who followed their banner.’ (Mackay 1838, Appendix 3)

An assault on culture and identity

David Morier’s Painting of the Battle of Culloden

The last phase of the Jacobite wars ended on the field of Culloden in April 1746 when a set-piece battle of limited manoeuvre was settled by superiority of numbers and fire-power. A bloody slaughter and ruthless pursuit followed. Many held the Highlanders to be heathen savages motivated by poverty and bloodlust, a general attitude that was encouraged by the press of the day as well as by political debate. There was a firm conviction in Whig politics that clanship and its uniform of the Highland garb should be destroyed, and that the Gaelic language, an enemy to church and state, should be rooted out. Property, progress and liberty formed the mantra for facing down the Highlander, the exiled Stewarts and Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The public image of the Highlander in the state of Britain was at its lowest. This is how we may understand, without condoning, the atrocities committed by the Hanoverian army and its commanders. They had been humiliated and out-manoeuvred by tactically mobile irregular forces, and there was a real and credible fear in 1746 that the Rising would break out again. Sufficient manpower on the Jacobite side had been absent from the battlefield and was now to offer a threat to the government forces, and individuals and clan units who had escaped from Culloden were suspected of raising and sustaining a guerrilla war. There followed the drive of the government forces to the West and a naval campaign of blockade and harassment up and down the Coast. Punishments and reprisals included high profile state trials, the execution of Lord Balmerino and Lord Kilmarnock and later Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat. The Earl of Cromartie barely escaped the same fate.

Legislation was part of the government policy to put an end to the clan system and to the clans as military units. The estates of Jacobite leaders were forfeited and the abolition of the Heritable Jurisdictions in 1747 deprived leading men of rights on which their power over their clansmen was supposed to rest; these jurisdiction were taken over largely by the sheriff courts. An arbitrary measure, the Disarming Act, was enforced with rigour and severity by an army of occupation. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1746 for the ‘Abolition and Proscription of the Highland Dress’:

‘That from and after the first day of August, One thousand seven hundred and forty-seven, no man or boy within that part of Great Britain called Scotland, other than such as shall be employed as Officers and Soldiers in His Majesty’s forces, shall, on any pretext whatever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland clothes, that is to say, the Plaid, Philabeg or little Kilt, Trowse, Shoulder-belts, or any part whatever of what peculiarly belongs to the Highland Garb; and that no tartan or party-coloured plaid or stuff shall be used for Great Coats or upper coats, and if any such person shall presume after the said first day of August, to wear or put on the aforesaid garments or any part of them, every such person so offending …. shall be liable to be transported to any of His Majesty’s plantations beyond the seas, there to remain for the space of seven years.’ (19 George II, Cap. 39, Sect. 17)

In terms of contemporary politics, it is understandable that a government should remove the weapon that had been lifted against it, but the removal and forbidding of Highland dress was a draconian measure and penalties were severe. The Act caused great resentment and distress which was given voice in propaganda songs by leading poets. The young Duncan Bàn Macintyre (1724-1812) of Glenorchy composed his Oran don Bhriogais (‘Song to the Breeches’) about 1747 in which he described the detestation of his countrymen for ‘foreign’ clothes, likened by him to sumagan or ‘saddle cloths’, and declaimed the cruel irony that the legislation extended to those Highlanders who had supported the Hanoverian side. Duncan Bàn described the sense of betrayal of himself and fellow-members of the government’s Argyll Militia: ‘Now we know about the sympathy that duke William showed us when he left us as prisoners …’ The Act applied only to Scotland and tartan might from time to time be seen in England as a symbol of Jacobite sympathy. The production of political souvenirs went on in England, such as miniature portraits of Prince Charlie in tartan or the popular line of ‘Jacobite’ wine glasses with enamelled portraits by Beilby of Newcastle. Tartan had of course become inescapably a political and Jacobite symbol and the statute reflected how effectively it had been used by Prince Charles Edward. The people of the Highlands and Islands were the victims.

As the years of proscription went by, the wearing of tartan certainly declined and, although the Act was renewed by parliament a few months before George II’s death in 1760, it seems largely to have fallen into desuetude. The ‘Act of Proscription’ was then repealed by Parliament without dissent in 1782 and was acclaimed by the poets. Duncan Bàn Macintyre took up the cudgel again: ‘We displayed in public our clothing, and who will call us rebels?’ – his contempt for English and Lowland dress mixed with expressions of freedom, honour, pride and identity. But in spite of literary comment from within the Highlands, tartan and Highland dress had drifted out of demotic use, and this makes it less easy to judge the extent to which tartan was the daily dress of everyman in earlier generations. The Act, in the context of contemporary social and economic change, had done its work.

Redemption and re-imagining identity

Countervailing pressure on public opinion was building up to change dramatically the public image of the Highlands in the second half of the eighteenth century. This is seen in a new literary attraction in the Highlands following the publication of the Ossian canon, a growing number of travellers publishing their experiences and descriptions of the Highlands, admiration for the role of the Highland regiments in the wars of the late-eighteenth century, the founding of the Highland Society of London in 1778, of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1780, and of the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland in 1784. Benjamin West’s commission, also in 1784, adds a graphic dimension to this process and is more easily understood and analysed in the context of these contemporaneous developments and the attitudes and interests that were a part and parcel of them.

Benjamin West’s self-portrait

Following the early use of Highland dress by the army’s Highland Independent Companies before the ’45, the kilt and plaid were adopted by those regiments raised for service in America during the Seven Years’ War or ‘French and Indian War’ of 1756-63. William Pitt persuaded the King to allow Highlanders to enter the military service of the Crown and the Duke of Argyll supported the concept as a means of getting rid of ‘disaffection’. Pitt’s speech to the House of Commons on 14th January 1766 has often been quoted, although this memorable and resounding passage is embedded in an otherwise insignificant speech:

‘I have no local attachments; it is indifferent to me whether a man was rocked in his cradle on this side or that side of the Tweed. I sought for merit wherever it was to be found. It is my boast, that I was the first minister who looked for it, and I found it in the mountains of the north. I called it forth and drew it into your service, an hardy and intrepid race of men! Men, who when left by your jealousy, became a prey to the artifices of your enemies, and had gone nigh to have overturned the state, in the war before the last. These men in the last war, were brought to combat on your side; they served with fidelity, as they fought with valour, and conquered for you in every part of the world. Detested be the national reflections against them! They are unjust, groundless, illiberal, unmanly.’

Those commissioned to raise regiments included Archibald Montgomerie, later eleventh Earl of Eglintoun, and Simon Fraser, attainted for his part in the ’45 but later pardoned. Montgomerie was obviously a Lowland laird but also brother-in-law of Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat and of Moray of Abercairney; he was able to recruit successfully in the Highlands and raised the 78th Highlanders for service in North America. A small portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds in the Royal Collection shows him as a Highland soldier in a bonnet with a high diced band and feathers and a red plaid round his shoulders. Montgomerie’s Highlanders and Fraser’s Highlanders, numbered as the 77th and 78th Regiments of Foot, totalled 1,460 men each and wore Highland dress. It has been estimated, some say conservatively, that up to 12,000 Highlanders were enlisted in the Seven Year’s War. The large number of military units being raised in the Highlands produced styles of Highland military uniform including bonnets, belts, swords and targes, the same details evident in Benjamin West’s painting.

Tartan as an expression of national identity evolved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Apart from its use and perception as traditional Highland dress, it emerged in the early-eighteenth century as a uniform of a conservative opposition to the Union of 1707 when antagonism and distrust adopted emblems of Scottishness. Armies opposing the London government, whether after the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689 or in 1715, drew their main tactical strength from the Highlands. The Grameid verse epic, imitating Virgil’s epic Aeneid, was an eye-witness account of the beginning of Dundee’s campaign in 1689 and describes the spectacle of the clan contingents gathering at the appointed place at Inverlochy dressed in bright and multi-coloured tartans and plaids. The association of tartan and Highland dress with Jacobitism was cemented in place, and a good example is to hand in the text of the so-called ‘Loch Lomond Expedition’. Opposition to an alien government together with a new sense of nationhood was particularly vigorously expressed in Gaelic song, for example, in ‘Song to the Highland Clans’ of about 1715 by Iain Dubh Mac Iain Mhic Ailein (or John MacDonald of Morar):

’S i seo an aimsir an dearbhar

An tairgeanachd dhuinn,

Is bras meanmneach fir Albann

Fo an armaibh air thus.

An uair a dh’èireas gach treun laoch

’Nan èideadh glan ùr,

Le rùn feirge agus gairge

Gu seirbhis a’ chrùin.

[‘This is the time in which the prophecy will be proved for us,

The men of Scotland are keen and spirited at the forefront and under their arms;

When every brave hero will rise in his splendid new uniform

In a spirit of anger and fierceness for the service of the Crown.’]

(Bàrdachd Ghàidhlig, 149-155)

The word tairgeanachd for ‘prophecy’ refers to the bardic belief in the restoration of the Stewarts – being seen as the first blow towards the revival of a Gaelic society in Scotland and Ireland – a traditional belief intensified by the politics of the Union in the early-eighteenth century. The message was generally understood and accepted by Gaels: ‘The nobles of the Lowlands will engage very eagerly in the Cause’, as John MacDonald put it. A Gaelic or pan-Celtic revival would be preceded by a national uprising in Scotland including Lowlanders and Highlanders, and victory in a great battle ‘beyond Clyde’. The Jacobite cause provided a new focus for the belief and sharpened the issues – and tartan gave it a uniform. Prince Charles Edward Stewart had been sent sets of Highland clothes by the Duke of Perth and Jacobite political leaders before the ’45, and he deliberately adopted Highland dress as a uniform for the army and encouraged and even directed that the foot soldiers, whether Highlanders or Lowlanders, wear tartan. On his arrival at Arisaig in July 1745, he questioned Alexander MacDonald of Dalilea, the most famous of Gaelic poets, about the comfort and convenience of Highland dress, and as the poet recorded:

‘He asked me if I was not cold in that habite [viz the Highland garb]. I answered I was so habituated to it that I should rather be so if I were to change my dress for any other. At this he laughed heartily, and next required how I lay with it at night, which I explained to him; he said that by wrapping myself so close in my plaid, I would be unprepared for any sudden defence in the case of a surprise. I answered that in such times of danger or during a war, we had a different method of using the plaid, that with one spring I could start to my feet with drawn sword and cocked pistol in my hand without being in the least incumbered with my bedclothes.’

Charles Edward Stuart by William Mosman

Portraits of the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries show contemporary styles of Highland dress worn by both Lowland and Highland leaders and lairds. The earlier portraits show the belted plaid and the later ones the belted plaid or the ‘little kilt’ – feileadh-beag. There is little or no comparison with modern tartans and setts but with few exceptions among the early surviving portraits the wearers are shown in shades of red. This was the colour that was most difficult to achieve in the dying process, evenly across a web of cloth, and therefore more expensive especially as deriving from exotic and imported dyestuffs such as cochineal. Research and dye-analysis in the National Museums has shown that early surviving tartans had been dyed with cochineal rather than native organic dye-stuffs. Descriptive epithets used consistently to describe tartans in Gaelic praise-poetry refer to reds and scarlets, in other words, to bright colours rather than muted colours. Praise of the warrior-hero dressed in tartan conformed to contemporary society’s expectation and was therefore couched in conventional terms which might not necessarily reflect the reality of an individual’s apparel. Red tartan of an expensive and preferably imported cloth was high fashion; colour and checks were mixed to suit the taste of the wearer or to accord with his sense of fashion.

The origins of Highland dress have been much debated; they seem to lie in an elaboration of forms of plaid or cloak-type outer garment, the so-called ‘mantle’ better known in late-medieval Ireland but also a trademark of early Highland dress. By the late-sixteenth or early-seventeenth centuries, a highly distinctive dress had emerged that stood for the Gaelic society of the Highlands and Islands. It can be compared to forms of dress refined in the late-Renaissance and to a heightened dress sense characteristic of the European Renaissance. A Gaelic song of the Civil War period printed in the MacDonald Collection of Gaelic Poetry (1911) leaves a strong impression of the success of the Highlanders in establishing their own iconic status and their own belief in it. The composer was a young woman whose beloved was marching to Auldearn with the Marquis of Montrose in 1645:

Clann Dòmhnaill nam faiche,

Nam bratach, ’s nan geur-lann,

Luchd nan còtaichean sgàrlaid,

Chit’ an deàrrsadh latha grèine.

Luchd nan còtaichean gearra,

Dha maith dhan tig fèileadh,

Luchd nan osanan ballach,

’S nan gartanan gle-dhearg.

[‘Clan Donald of the parade-grounds, of the banners and of the sharp blades,

Men of the scarlet coats, to be seen shining on a day of sun,

Men of the doublets for whom the plaid is so becoming,

Men of the speckled hose and of the bright red garters …..’]

Later portraits such as those of John Campbell of Ardmaddie by William Mosman (1749), Norman MacLeod of MacLeod by Alan Ramsay (1748), or Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat (c.1775), show their subjects in full Highland dress within the period of Proscription. These are bold statements in terms of British politics, the sitters appearing to assert a right to wear tartan. Another element of these compositions seems to be the Highlander as classical archetype, for example in the portrait in Dunvegan in which Norman MacLeod, known to tradition as ‘The Red Man’, was painted in a mood of senatorial and classical nobility, in the pose of the Apollo Belvedere, at the time the most admired of all the known sculptures from antiquity. Pompeo Batoni’s (for Scotland) exceptional portrait of Colonel John William Gordon of Fyvie, soldier and Member of Parliament, was painted in Rome in 1766, the subject in his thirtieth year, in military uniform with kilt and plaid folded toga-like round his body. Here we have a Classical hero or inheritor of Classical values, the seated statue of Roma to his left offering him the orb of command and the wreath of the victor. Campbell of Ardmaddie in a doublet and plaid in red and black tartan, with sword, dirk, pistol and powder horn, displays this ambivalent but iconic image, dressed and accoutred as though the Act of Proscription supplied his dress code! He was a lawyer and banker in Edinburgh, Principal Cashier to the Royal Bank of Scotland, moving in the fast-stream of British commerce and choosing to have himself painted in Highland dress with the traditional arming of the Highlander. He was a popular figure and the subject of a bardic tribute by the Gaelic poet, Duncan Bàn Macintyre. He was certainly overtly Whig and Hanoverian in his politics but, like Macintyre, probably royalist in his native Gaelic mindset and upbringing, and ever mindful perhaps of the traditional ‘prophecy’ of a Gaelic resurgence. Before even the death of Bonnie Prince Charlie himself in 1788, the Highlander had emerged as a heroic and ‘classical’ figure, the legatee of primitive virtues.

Portrait of Norman MacLeod, the “Red Man”, circa 1747, by Allan Ramsay

The Ossian factor

One of the less tangible but nonetheless dramatic moments in this process of rehabilitation or reincarnation came in 1760. The publication of Fragments of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland and translated from the Galic or Erse Language may seem an odd benchmark for the painting but it supplies in a sense the backdrop against which some of the style of West’s scene is created. The latter however is different in important respects. A brief comment from 1919 by Peter Hume Brown, the first Professor of Scottish History in Edinburgh University, reminds us of the effect of Fragments of Ancient Poetry:

‘It struck the most resounding note in European literature of the eighteenth century, and it laid its spell on the greatest man of action and the greatest man of thought, Napoleon and Goethe.’

The impact of James Macpherson’s ‘Ossian’ in all its facets has begun to be more fully assessed in a scholarly atmosphere and without prejudice. The status of the poetry of Ossian as ‘translation’ and its intrinsic merits or demerits have continued to be argued over, but the wide-ranging influence of the Ossian phenomenon can now be recognised. The national and then international popularity of the poetry of Ossian grew rapidly following its first publication between 1760 and 1763 and remained strong for approximately the next half-century, in spite of a shift from acclaim to controversy. The publications ushered in the Romantic era in Europe, inspired poets, playwrights, politicians, musicians and artists, and were transformed into new formats. Powerful emotions emanated from the bard, his speeches and moods, against the backdrop of a wild – ‘sublime’ – landscape of mountains and torrents and storms. These were ingredients which strongly appealed to the contemporary mind and inspired the revival and creation of national epics.

Illustration from the title page to Ewen Cameron’s annotated, 1777 translation into heroic verse of James Macpherson’s Fingal.

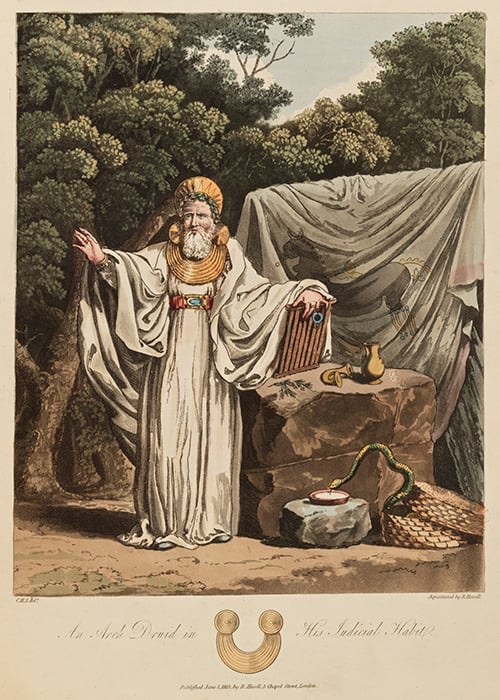

Setting aside accusations of forgery or fraud, the poetry was not translated from an ancient Gaelic ballad as claimed by Macpherson but was a free prose rendering of portions of Ossianic ballads then surviving in oral tradition in the Highlands. This distinction, so vital to modern scholarship, was of less immediate significance for Enlightenment Europe who read in it the voice of a Celtic past for which there was growing sympathy and interest. Preoccupied with social change and the progress of mankind from ‘rudeness’ to refinement, peripheral communities within Britain and Ireland now supplied ideal objects of study. And never before had western society examined its past in such depth and offered up details in scholarly and antiquarian research, literature and art. This, of course, included material culture. From the examination of antiquities in the field, pioneered by such names as William Camden and William Stukeley, succeeding generations moved to reconstruction. This of course informs West’s own construction of early Scottish history and continued with works which were at the time accepted as authoritative such as Meyrick and Hamilton’s Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Islands published in 1821. Here the image of West’s ‘Fitzgerald’ in saffron neo-classical tunic is reproduced as the dress of druidic Celts.

An Archdruid in his Judicial Habit from Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Isles (1815) by Samuel Rush Meyrick and Charles Hamilton Smith

Enlightenment man could begin to measure themselves against other societies, contemporary and ancient, and against their mores and cultural practices; and it could be confirmed that the Highlanders were an alien and separate race. We might assume that Rousseau guided this discourse; in his search for the essential goodness of mankind, he postulated that the ‘noble savage’ must exist as archetype or a people belonging to an Age of Innocence uncorrupted by European civilisation. I suggest that we see in the Benjamin West canvas and a reaffirmation of Irish pedigree a particular British discourse on antiquity. It was perceived that the Gaelic civilisation of Scotland and Ireland supplied figures from a perceived Golden Age, a classical civilisation apart from the classical civilisation of Greece and Rome, and arguably also freed up from the saints and scholars of early Christian Ireland. We have a noble and heroic scene with chieftain and retainers in pagan garb and unencumbered by ideologies of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation which had dogged antiquarian investigation in its early stages.

Rondeau and Crunluath

Angus Mackay’s glossary of musical terms in his Collection of Ancient Pìobaireachd brings us back to the introduction in considering Benjamin West’s painting. It marks a particular moment in time in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century rehabilitation of the Highlander and the transformation of Highland dress from the mark of the rebel into an icon of national identity. The painting is a dramatic portrayal of that moment as well as of a contemporary view of Gaelic antiquity. In the wake of the Ossian phenomenon, Scotland’s past, in the absence of any other sure-footed history, was being romanticised and almost inevitably located in the Highlands. This was a landscape of heroic action and idealistic endeavour, and, first and foremost, a landscape of the mind.

Engraving of Death of a Stag

On the heroic and patriotic side, Highland soldiers continued to distinguish themselves in the Napoleonic Wars and achieved a reputation really out of all proportion to the numbers involved. Some campaigns featured them more strongly than others, for example, the British expeditions to Holland in 1799 and to Egypt in 1801 under the command of the popular leader, Sir Ralph Abercrombie. The victory at Alexandria in 1801 was commemorated in a medal designed by Benjamin West in which the centrepiece is another ‘Fitzgerald’ figure in Highland military-style dress and a motto in Scottish Gaelic. On the literary and romantic side, Ossian was joined by Rob Roy and Fergus MacIvor and a past of the mind created by Sir Walter Scott. His Jacobite novel published in 1814, Waverley, or ‘tis sixty years since, was received with admiration and adulation. It put a seal on this process and looked back in such a way as to mask the subtler shades and gradations of change. The figure of the kilted Highlander in his badge and uniform of tartan might be assumed to be a figure almost of antiquity, whereas he had been created in the course of the wars of the antecedent generation. The political and cultural transformation was complete when the King’s visit in 1822 was stage-managed as an entirely Highland affair. The transformation draws a veil over the grimmer realities of economic decline and emigration and reduces complexity to caricature. One hundred years on from 1745, the publication of the sumptuous two quarto volumes of the Clans of the Scottish Highlands by Ackerman of London put another seal on the process of transformation and rehabilitation. Seventy-four colour plates by Robert Ronald McIan (1807-1856) illustrate historical forms of costume, each ‘portrait’ named for a family or clan and accorded a particular sett or tartan specific to his or her name.

Inside the National Gallery, Edinburgh

Benjamin West’s magnificent painting on its canvas of 12 ft. by 17 ft. provides one of the most stunning portrayals of what might be described as the reincarnation of the Highlander and it marks a key moment in time for this process. It supplies an insight into the extraordinary process whereby villain was turned to hero and traitor into national icon. This transformation which has had such a lasting effect on Scottish culture – or how it is perceived – took place therefore within a generation of the Act of Proscription of 1747, through the lifting of the ban on Highland dress in 1782, and onward to the crowning moment when the Highlander took the centre-stage in the Royal Visit of 1822.

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig

15 An Dàmhair 2023

Sources and Reference

Bell, A S, Editor, The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition. Essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and its Museum, 1780-1980. Edinburgh: John Donald 1981.

Cheape, Hugh, Tartan: the Highland habit. Third Edition. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland 2006.

Cheape, Hugh, ‘The Culture and Material Culture of Ossian, 1760-1900’, Scotland’s (Macpherson’s Ossian) Volume 4.1 (1997), 1-24.

Cheape, Hugh, ‘The Culture and Material Culture of Jacobitism’, in Michael Lynch, Editor, Jacobitism and the ’45. London: Historical Association 1995, 32-48.

Gaskill, Howard, Editor, Ossian Revisited. Edinburgh University Press 1991.

Grant, I F, and Hugh Cheape, Periods in Highland History. London: Shepheard Walwyn 1987.

MacDonald, Rev A, and Rev A MacDonald, The MacDonald Collection of Gaelic Poetry. Inverness: Northern Counties Publishing Company 1911.

Macdonald, Donald, Lewis. A History of the Island. Edinburgh: Gordon Wright Publishing 1978.

Mackay, Angus, A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd or Highland Pipe Music. Edinburgh: MacLachlan and Stewart 1838.

Mackenzie, Alexander, The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer (Coinneach Odhar Fiosaiche). Stirling: Aeneas Mackay 1924.

Mackenzie, John, Sar-obair nam Bard Gaelach, or the Beauties of Gaelic Poetry. Fourth Edition. Edinburgh: MacLachlan and Stewart 1877, 359-361.

MacLeod, Angus, Editor, The Songs of Duncan Bàn Macintyre. Edinburgh: Scottish Gaelic Texts Society 1952.

Matheson, William, ‘Traditions of the Mackenzies’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness Volume 39-40 (1942-1950).

Miller, Hugh, Scenes and Legends in the North of Scotland, or the Traditional History of Cromarty. Second Edition. London: Johnstone and Hunter 1850.

Munro, R W, Highland Clans and Tartans. London: Octopus Books 1977.

Quye, Anita, and Hugh Cheape, John Burnett et al., ‘An Historical and Analytical Study of Red, Pink, Green and Yellow Colours in Quality 18th and Early-19th Century Scottish Tartans,’ in Dyes in History and Archaeology 19 (2004), 1-12.

Skene, William Forbes, Celtic Scotland Volume III. Edinburgh: David Douglas 1876.

Statistical Accounts, being printed reports from all the parishes of Scotland, including The Statistical Account of Scotland, conventionally called ‘the Old Statistical Account’ or OSA printed in 21 volumes, 1791-1799, and The New Statistical Account or NSA, 1838-1845, printed in Edinburgh in 1845 in 15 volumes.

Stewart of Garth, Colonel David, Sketches of the Character, Manners and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland. Second Edition. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable 1822.

Sym, Colonel John, Editor, The Seaforth Highlanders. Aldershot: Gale and Polden Ltd 1962.

Thomson, Duncan, Editor, Benjamin West and the Death of the Stag. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland 2009.

Watson, William J, Bàrdachd Ghàidhlig. Specimens of Gaelic Poetry 1550-1900. Third Edition. Stirling: A Learmonth and Son 1959, 149.