Part 1 – Cabarfeidh and the Tahitian

Hinchingbrooke House in Huntingdonshire has seen many remarkable sights in its history. Here Oliver Cromwell had played as a child and – according to legend (sadly, most probably apocryphal) – presaged the Civil War by winning a fight with the young Charles I. By 1774 the house had become the seat of John Montagu, First Lord of the Admiralty and 4th Earl of Sandwich. Had one been present then, one would have been treated first to a Tahitian barbecue and then, following on from the house party, in what is now Leicester Cathedral, to the unusual sight of a handsome Pacific islander, no doubt wearing a sword and dressed in the powdered wig, velvet and silks of an 18th century gentleman, transfixed in “wild amazement” by the sights and sounds of a private performance of Handel’s oratorio, Jephtha. His name was Ma’i – known to posterity as “Omai”.

Omai is said to have stood in awe throughout, and one can well imagine the alien wonder of such a spectacle to the eyes and ears of a Tahitian, transported in his early 20s – almost as if by a time machine and to another universe – with the very best of intentions, but to 21st century eyes, cruelly and without foresight, from the as yet unspoilt islands of Tahiti to the teeming and exhilarating urban bustle of a booming mid-18th century England.

Sandwich’s wife had a few years before been declared insane. With Sandwich himself performing on the kettle drums, also present and in her place most probably would have been the Earl’s mistress, the talented singer Martha Ray – five years later to be shot dead by a jealous lieutenant soldier in the foyer of the Opera House at Covent Garden.

The young Ma’i had been brought to England by Captain James Cook not just as a physical specimen or novelty – for it seems he was in fact very fond of the young man – as part of his Second Voyage. Back in England, he was then left in the care of Cook’s fellow Royal Society member, the famous naturalist and polymath Sir Joseph Banks. There, through his charm, quick wit and exotic good looks, he became a huge favourite with the most cultured elite of aristocratic London society. (He even went on a trip to see “the Cambridge professors” – and to his credit this seems to have been the trip he enjoyed most of all).

What is less well known is that Cook’s patron (who even sponsored him for his Royal Society membership) was the Mackenzie chief, Kenneth Mackenzie, Lord Fortrose and last Earl of Seaforth – and that Cook had learnt his revolutionary maritime surveying methods from another clan member, Murdo Mackenzie (hydrographer to the Admiralty, like Cook a close friend of Banks and in fact a member of my own immediate family line).

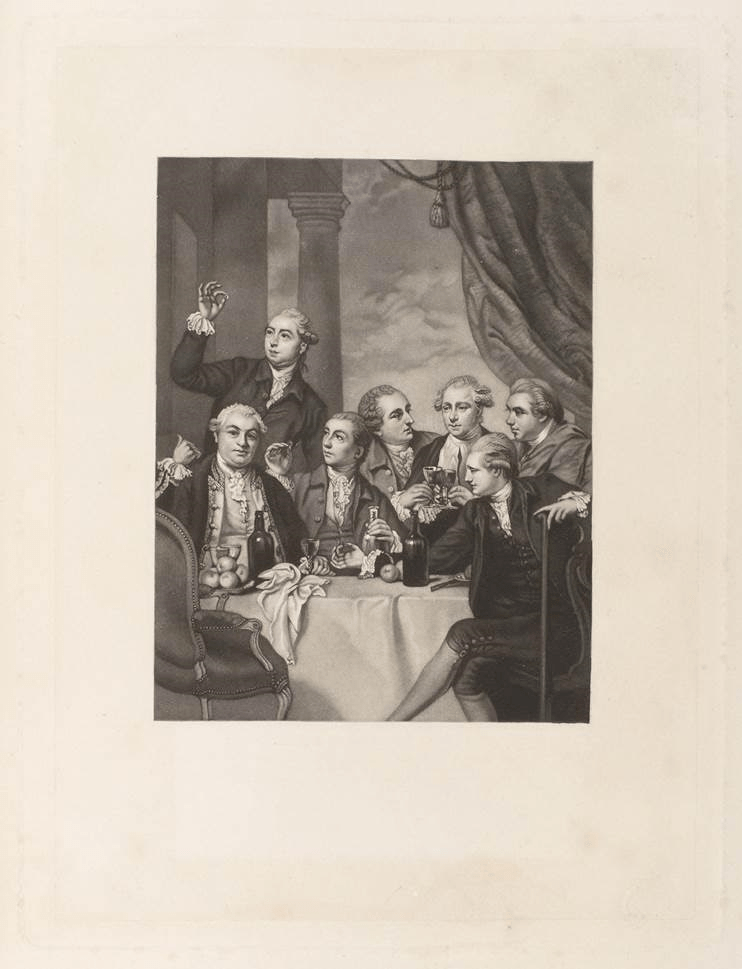

Seaforth was most probably introduced to Omai at the Royal Society dinners which Banks organised and to which they were both regularly invited. An integral part of Sandwich, Cook and Banks’ cultured scientific circle, he was like Banks also a member of the Society of Dilettanti, and had interests which ranged from collecting Roman antiquities to patronising the very newest and most sophisticated of developments in music and art. In May 1770 he had even invited the 14-year old Mozart, with his father Leopold, to put on a concert party at his seaside villa (a house which my brother and I have identified as most probably what was then known as the Casino di Frisia and is now the Villa Pavoncelli) on the Posillipo coast in Naples – with Sir William Hamilton accompanying them on the violin and Seaforth looking on as Vesuvius tinted the sky pink and smoked and rumbled alarmingly across the bay.

Like Omai, who when taken swimming off Scarborough had his splashing “exuberance” and tattoos remarked upon – and who in the early morning sunbeams was described as having a “cutaneous gloss”, and as being “like a specimen of pale moving mahogany” – Seaforth was a keen swimmer and these morning concert parties were held regularly by him after taking friends out in his boat to go swimming in the bay of Naples.

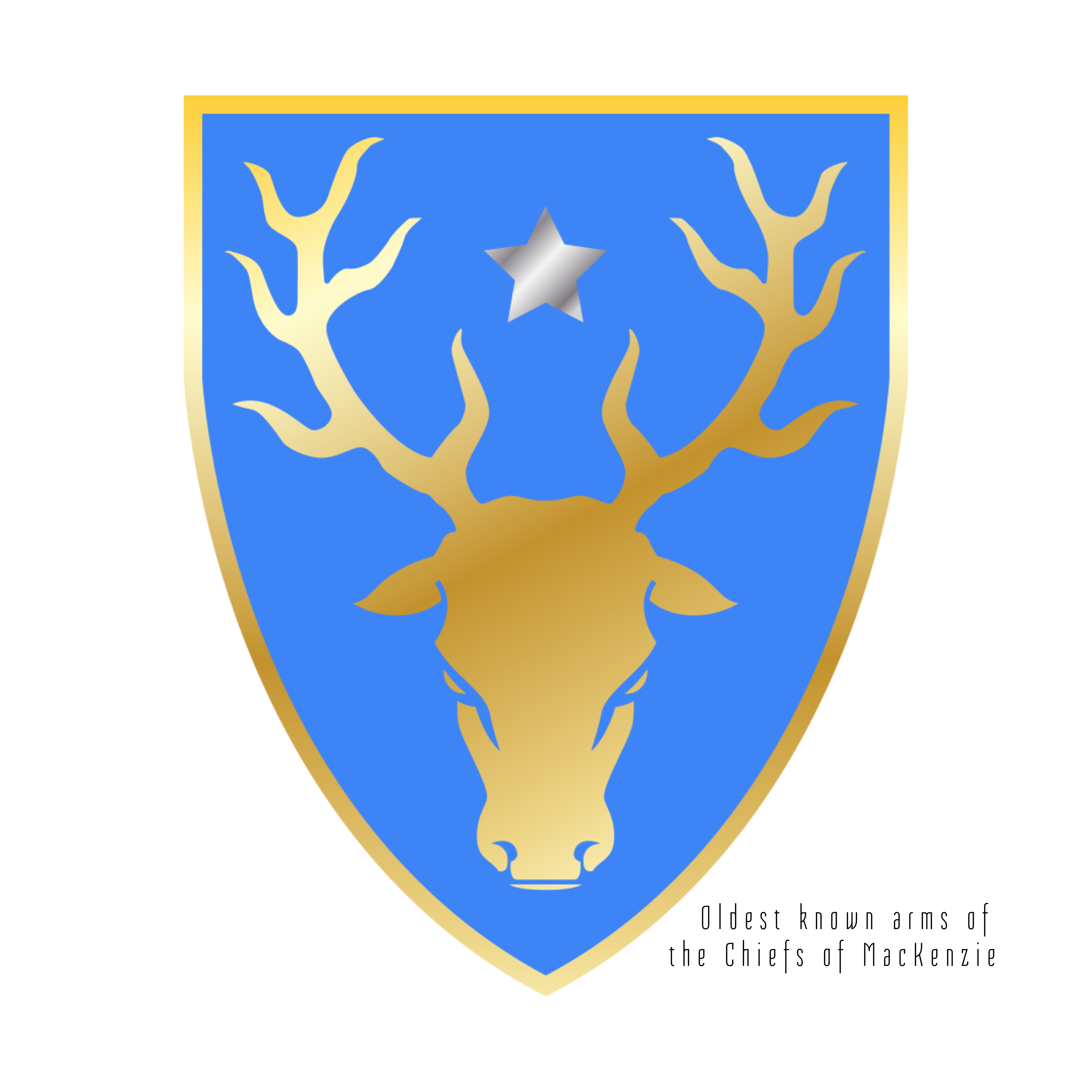

My detective work reveals that a recently auctioned painting The Bay of Naples from Posillipo by Pietro Fabris, dating from circa 1770, is likely to be a view of Seaforth’s villa, painted during one of his morning bathing trips and concert parties. The awning above the villa’s roof-top terrace is coloured blue and gold – the family’s heraldic colours – and the small boat approaching the villa is most likely that of Seaforth himself, displaying a flag emblazoned with the Cabarfeidh.

It seems that Banks kept a very detailed journal of a trip which during the young man’s two year stay he made with him and Seaforth on Sandwich’s yacht the Augusta. Not only did they have pease pudding and beer at Greenwich Hospital and go shooting birds on horseback (somewhere near the Isle of Wight – which was where Sandwich left them), but they also went pick-nicking and rowing through marshes and also to the theatre together in the evenings.

When they were in Greenwich, they visited the Observatory and went inside the still surviving Camera Obscura. Banks (who stayed outside) records hearing them inside – with Sandwich exclaiming something which he recorded with simply a dash, Seaforth crying “a cara” (oh dear in Italian) and Omai (in Tahitian) “oh how strange!”. Having a few years ago visited the similar camera obscura in Edinburgh, I remember using cards to pick up projections of people as if they were insects, and having since discovered Banks’s journal I would hazard a guess that Omai and Seaforth were doing just the same thing!

During his stay in London Omai is said to have seduced the famously beautiful Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire with his charms. As we shall see, another who fell for him was the transvestite Chevalier d’Eon, one time secretary to Seaforth’s cousin, the Chevalier Alexander Mackenzie Douglas.

Banks recruited his botanical artists for his house in New Burlington Street (where he lived before he bought 32 Soho Square in 1776) as soon as he got back, in 1772, from his voyage to Iceland with the Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander (which appears to have involved a stopover at Stenness in Orkney where they must have met their friend Murdo the hydrographer and perhaps also his cousin Captain Patrick Mouat, whose father James and Mackenzie mother were the laird and lady of Stenness). Both Banks and Solander, in 1774, were sponsors of Murdo for his membership of the Royal Society, and it seems that these connections must have led Banks to recruit a near cousin of Murdo, Daniel Mackenzie – a man who later became a botanical engraver to Lieutenant William Bligh. When he was living at his house in St Anne’s Court (where he is recorded as living in 1784), off Dean Street (and close toBanks’s later house in Soho Square, where Banks kept a herbarium), Daniel made many of the engravings for his famous Florilegium. Just across the road from him was Carlisle Street, where Banks stabled his horses behind no. 32, and it seems that it was from here that Omai was to go horse riding with the Chevalier d’Eon, the Secretary to Seaforth’s cousin (a son of Colin Mackenzie, 2nd of Kildun), Mackenzie Douglas. When Omai was in London “there was talk about some capers with a well-known London transvestite”. It is not specified who this was, but since I cannot imagine there were too many well-known London transvestites in the mid-1770s, it seems to me that the only likely candidate for the latter is d’Eon, who was in exile in London from 1766 to 1777. (The Chevalier d’Eon was a fervent admirer of Rousseau, which presumably is something he may have acquired from Mackenzie Douglas, whose employer Prince Charles Edward Stuart was a similar admirer of the philosophe – and which is presumably why d’Eon was interested in Omai as a “noble savage”). So yet again Omai seems to have been intimately involved in the Mackenzie circle. Omai would not have found anything unusual in d’Eon’s manner of dress, for apparently there were transvestites on Tahiti, known as mawhoos. An amusing story is recorded of how Omai could not cope with riding a horse, butbecause he was a noble Tahitian the nobility in England automatically assumed that like them he would be able to do so, when they didn’t even have any horses on Tahiti!

In 1776 James Cook set sail in order to return Omai to his home in the Tahitian islands, on his Third Voyage. Sailing with him on the Resolution, I discovered, as an able seaman was a hitherto unidentified Daniel Mackenzie (according to the muster list, born in Inverness circa 1743), who was surely Banks’s botanical engraver. And sailing on the Resolution’s sister ship, the Discovery, was yet another such cousin, the 15-year old Midshipman Alexander Mouat, whose son was later to marry a cousin of yet another member of this circle – the famous horologist and longitude prize winner, Thomas Mudge. It must have been as part of this circle that the most famous of Mackenzie explorers, Sir Alexander, studied developments in longitude during the interval between his own two voyages of exploration.

When they finally arrived in the Tahitian archipelago, on the night of 23rd November 1777, Midshipman Alexander Mouat tried to escape to Omai’s island of Huahine with his Tahitian friend “Pedro”and the gunner Thomas Shaw, when they were moored at Raiatea,Omai’s home island just to the west of Tahiti, by paddling north to Taha’a then Bora Bora and Tupai in a canoe. This was shortly after, on 2nd November, they had dropped off Omai at Huahine, and where Omai was settled and they built him a house, in which before they departed he treated the ships’ officers to a demonstration of his playing the organ and of his “electrifying machine” (most likely a Leyden Jar, a recently invented device that stores static electricity).

Since the young midshipman had made a Tahitian girlfriend who lived on Huahine and whom he must have met through his friends Omai and Pedro, much to Cook’s solicitous embarrassment and regret he wanted to stay there and not come back to England. (Alexander’s father was Captain Patrick Mouat, a man who was a cousin of Murdo the hydrographer and whose nephew Murdo Mackenzie the younger had circumnavigated the globe with him and Admiral Byron in 1764-6; the Captain of the Discovery was Charles Clerke who had sailed with them). Cook however secured Alexander’s capture by means of hostage-taking of Tahitians. Briefly punished by being stripped of his commission and put to work “before the mast” (that is, with the ordinary sailors), Alexander later became a Lieutenant and then a Commander, but died from fever in the West Indies in 1793. Cook, himself killed soon after leaving Omai as a consequence of an ill-judged incidentin Hawaii, could never have foreseen that they would probably all have been luckier had they stayed on Omai’s island.

Young Midshipman Mouat’s native islander girlfriend was herself from Huahine, the very island to which Omai was returned. It is very possible that he had been Omai’s companion on board the Discovery. It is true that Omai sailed on the Resolution with Cook and Daniel Mackenzie, and the latter’s colleague the surgeon and naturalist William Anderson was a good friend of Omai (who called him “Asoso”), and his first mate David Samwell kept an interested eye on Omai throughout the voyage. However Omai, known to the sailors as “Jack”, was also the Discovery’s interpreter and is recorded as having preferred the company of youths – and so the young midshipman may well secretly have received help from Omai in relation to his attempted escape. In fact, since Huahine is only some nine miles long, it seems highly likely that Omai was a friend or relative of the girlfriend’s family on the island. (It is interesting to note not only that the name of one of the wives of of Teha’apapa I, the paramount ruler of Huahine from 1760 to 1790, was Mato, and many of their immediate descendants’ names began with the prefix Ma-, but also that immediately to the south of Huahine is an island named Maio). For various reasons, William Anderson may well be the same man as one of that name who witnessed the baptism of twins to a John Mackenzie, a weaver or linen draper and close relative of Daniel the botanical engraver, in Inverness in 1745.

In Cook’s last letter to Sandwich, written towards the beginning of the Third Voyage, on 26th November 1776 when they were at the Cape of Good Hope, he wrote:

“We are now ready to proceed on our Voyage, and nothing is wanting but a few females of our own species to make the Resolution a compleate ark for I have added considerably to the Number of Animals I took onboard in England. Omai consented with raptures to give up his Cabbin to make room for four Horses – He continues to enjoy a good state of health and great flow of spirits, and has never once given me the l[e]ast reason to find fault with any part of his conduct. He desires his best respects to you, Dr Solander, Lord Seaford [sic] and to a great many more, Ladies as well as Gentlemen, whose names I cannot insert because they would fill up this sheet of paper, I can only say that he does not forget any who have shewed him the least kindness.”

We learn from Cook’s journal that Omai had burst into tears andpleaded with them not to leave him back in the Tahitian islands, but instead to be taken with the crew back to London again. And his two, similarly well-liked, Maori boy companions, Taiaroa and Koa, also in tears, twice jumped overboard from their canoe to swim back to the ship, and had to be physically carried ashore.

Omai was most certainly – with his new house at Fare Harbour on Huahinebrimming full of what to anyone, let alone the Tahitians, must have been deemed very exotic and valuable possessions (as we have seen, they included a Leyden Jar and an organ, and it also seems that Omai had two horses, muskets, cutlasses, cutlery, crockery, furniture, fine clothes and a suit of armour, in which he went horse riding) – left in a very exposed position. Threatening the local Tahitians with the suggestion that George III would take revenge if anyone in Tahiti harmed him after they had left seems to me a very insufficient deterrent, and my guess is that the Tahitian islanders later covered up for the fact Omai had been killed. In 1788 the British transport the Lady Penrhyn visited Huahine and recorded in her log that Omai had died and then, during the Bounty’s visit to Tahiti in 1789, Lieutenant William Bligh and his crew were variously told that Omai had shortly after Cook’s departure repelled an invasion and died “about 30 months” (and according to another account “about four years”) after Cook’s departure, of fever. Given the timescale, Omai’s having been their protege and the threat of the King’s revenge, this may well have been a convenient excuse – and it is perhaps telling that all of Omai’s possessions had in the meantime gone missing.

One can only but look back on Omai’s life with sadness. It seems more likely than not that he was killed by his fellow islanders shortly after the ships’ departure – out of envy – and that (although I see that his Polynesian name Ma’i translates as sickly, devoid of strength or slightly ill), his having survived the rigours of introduction to an alien society in a dirty and overcrowded London, and two long and arduous voyages, he did not die of disease.

When Omai saw a meteor we learn that he thought it was his god travelling to England and the sailors all laughed at him; he then got upset and angry. We also learn of the fun made of his bow, of his words to George III when introduced (“How do King Tosh”), and of the sad farewell scenes in Tahiti. Any historians who criticise any aspects of his proud behaviour in the circumstances of what happened to him must surely be very lacking in human empathy, and it would take a callous commentator not to see the personal tragedy and the whole episode of Omai as one which is upsetting and disturbing. However, in his friendship with Seaforth, a cultivated and humane man of his time, who was kind to Omai and whom we know Omai remembered with fondness, we can at least record some happy moments in this poor man’s short, but eventful life.

2023 Addendum: Described as “one of the most important, influential portraits in the history of British art”, Reynolds’ Portrait of Omai was given pride of place by the National Gallery in London after the portraits acquisition by UK’s National Portrait Gallery and the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Article written by Kevin McKenzie