This article is a continuation of The Raven’s Skull – Deciphering the Legend of the Birds: history preserved in the oral tradition of the Mackenzies, by Kevin McKenzie. Lavishly-illustrated, mostly with Kevin’s own photographs again, and with a link to a YouTube video of atmospheric readings from medieval Persian poetry (whose relevance will become apparent), this article sets out some of his remarkable new findings, which support and expand upon his previous piece of historical detective work.

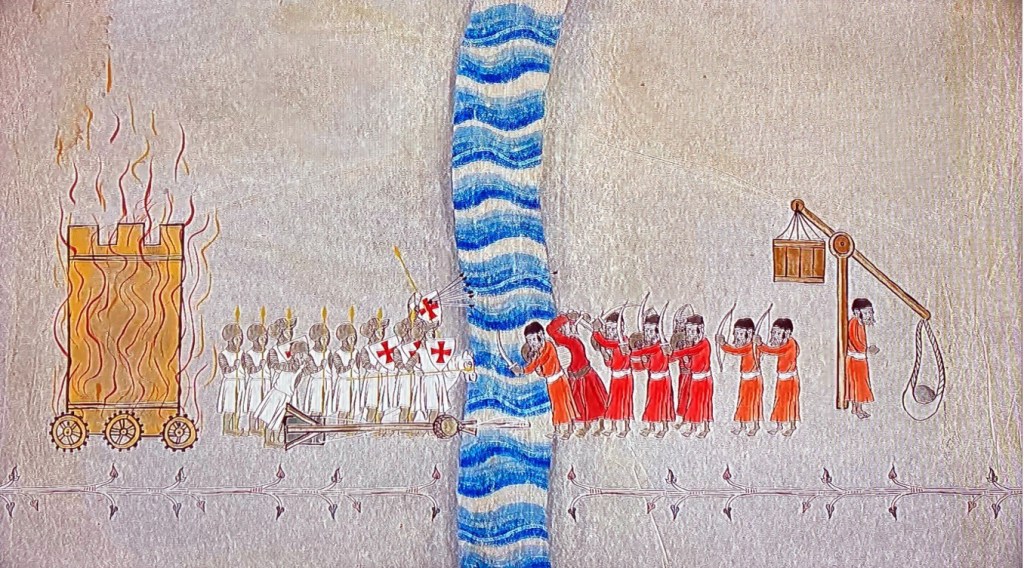

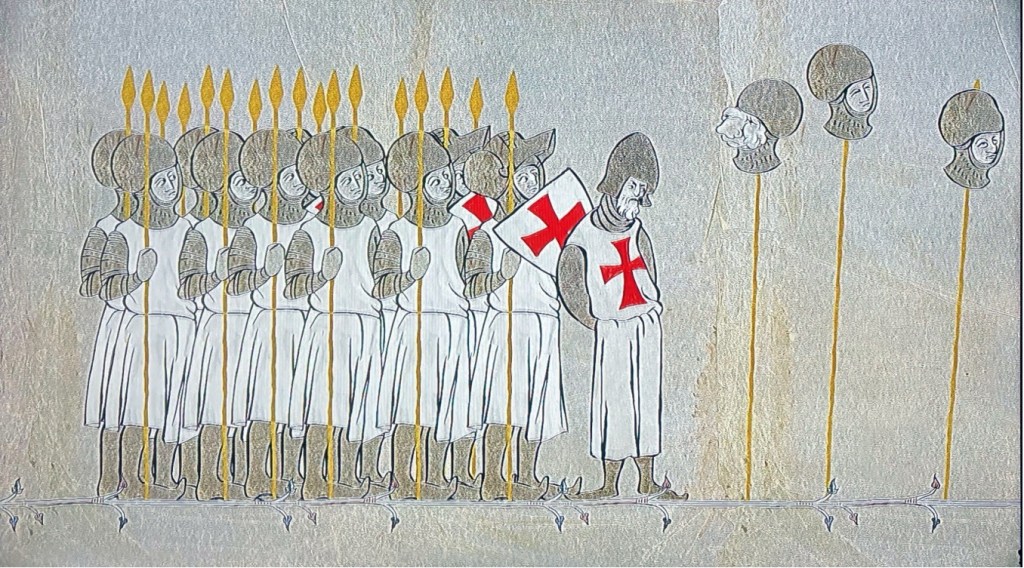

Where any image in this article is uncaptioned, it was taken by the author himself, in August 2022, and shows the Rassemblement Medieval d’Aigues-Mortes, a festival which took place in August 2022 to commemorate King Louis IX and his knights, and the foundation of the town, at the walled crusader fortress of Aigues-Mortes. This was the port from which Louis and his party of crusaders set sail in August 1248. All other images, such as the above, are either in the public domain or licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence.

Kish Island in the Persian Gulf, off the southern coast of Iran, has been known by various names throughout its history, including Kamtina, Arakia, Arakata, Kisi and Ghis. In 325 BCE, Alexander the Great commissioned his admiral, Nearchus, to explore the Persian Gulf, and Nearchus’s Arakata contains the earliest known mention of Kish. Later, Marco Polo mentioned ‘Kisi’ in his account of his travels to the court of the Emperor Kublai Khan, and it has even been suggested that the pearls worn by the Empress originated from there, the island being famed for these.

In this article, I explore the mysterious significance of this island in Mackenzie family history, and, with it, how I stumbled upon some amazing connections which provide yet further, compelling evidence to support my conclusion (which I made several decades ago) that the Mackenzies’ foundation legend for Eilean Donan Castle (‘The Legend of the Birds’) must have derived from the family’s mid- to late-13th-century ancestral progenitor, Kenneth Macmathan, having participated in the Seventh Crusade – that of King Louis IX of France (Saint Louis). In doing so, I revise my earlier suggestion that Kenneth must have learned the story of Prince Keish and his cat whilst in Damietta, at the court of al-Kamil, the Sultan of Egypt. This is because I have since unearthed an astonishing piece of much more specific evidence, which strongly suggests that Kenneth learned of it in the following way, instead.

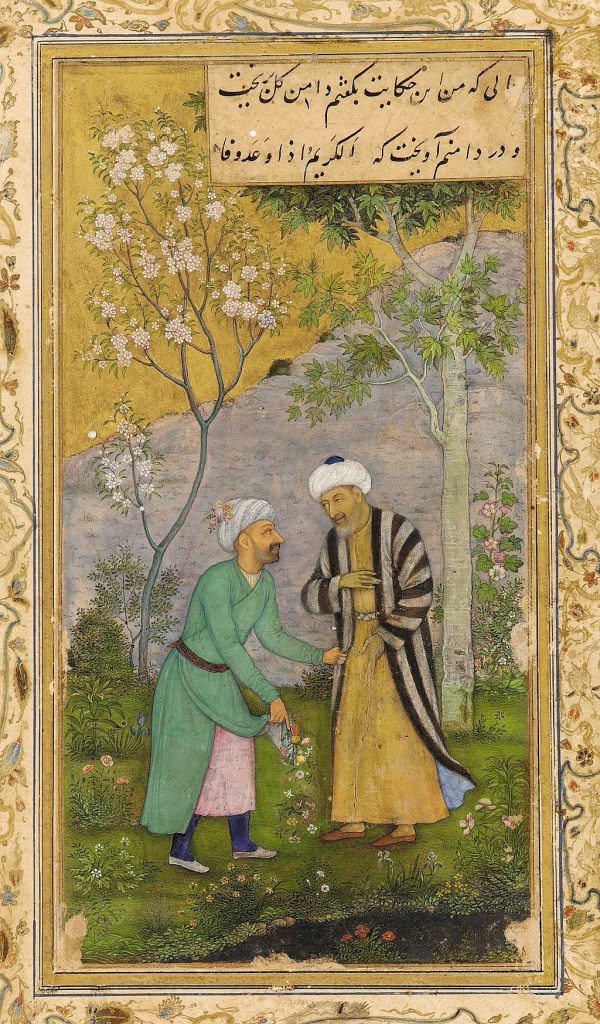

Sa’adi the Poet

Sa’adi Shirazi (‘of Shiraz’) was a famous Persian poet of the 13th Century. My detective work has now turned up extremely strong evidence that the ‘The Legend of the Birds’ must have derived much of its essential content from a surprising encounter between Kenneth Macmathan (a patronymic meaning ‘son of the Bear’ – the appellation of his hunchbacked father, Angus), whilst he was on Louis’s crusade, and Sa’adi the poet. And to add to this surprise, such an encounter must have taken place when Sa’adi was held as an enslaved captive at the famous crusader castle of Krak des Chevaliers, in what is now Syria.

After first showing how it is very likely that Kenneth would have met Sa’adi, I will then go on to show how it was such an encounter which must have given rise to some of the specific detail of the oral tradition of the Legend, which is the foundation legend of Eilean Donan Castle. I had already set out the details of the Legend in my article, ‘The Raven’s Skull’, which was published in a Mackenzie clan society magazine (in 2018).

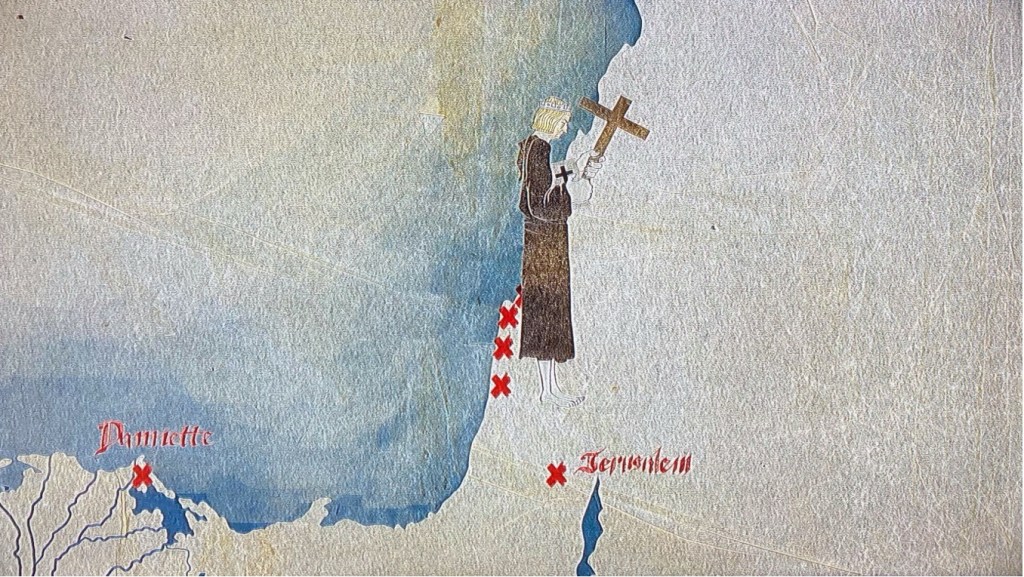

Matthew Paris’s 14th-century Chronica Majora records that Hugh de Chatillon, Comte de Saint Pol, constructed a wonderful ship (‘navis miranda’) in Inverness – and, as I showed in The Raven’s Skull, with this ship he must have taken a party of crusaders to join those of King Louis, who set sail from the newly built crusader-fortress and port of Aigues-Mortes.

My brother Andrew published his scholarly history of the Mackenzies, ‘May we be Britons?, back in 2012, and I researched the medieval section of this. The two of us were then keen to visit Aigues-Mortes. However, in the event, when we arranged this, a somewhat complicated journey presented us with a badly delayed train on one of the final legs of our successive connections from Annecy in Haute-Savoie (where, at the picturesque Talloires, just down this Alpine lake, we had been staying in one of our very favourite holiday destinations). So, we only arrived in Aigues-Mortes late in the evening, after having to complete the final leg of our journey by means of a long taxi ride. Yet, serendipitously, after quickly checking into our hotel, we found, some way off the main, central square of the town, an Indian restaurant. This was one of the very few restaurants still open, and we were lucky enough to find a table there, outside, on the narrow street. Like all the other streets in the marvellously preserved and wonderfully atmospheric little walled town, it was part of the grid-pattern of streets which had been constructed in King Louis’ reign. During our dinner, a fantastic medieval costumed procession suddenly appeared, and made its way straight past the table where we were sitting. The spectacle was complete with standard bearers, drummers, medieval bishops, knights and their ladies, a king and queen, a princess and her attendant, soldiers, peasants, dogs, sheep, and a miniature pony. When we had finished our meal, we followed the crowds and found that this costume carnival led on to one of the main 13th-century gateways which punctuated the walls, and opposite what a couple of days later we saw to be the town’s pink salt lake, the Etang de la ville. Above the gateway and its adjoining walls, there then began a spectacular firework display. When this was over, and most of the crowd of temporary tourists had dissipated, we followed the actor-participants, and joined them, letting their hair down, in a makeshift medieval inn, serving beer – which had been constructed in the form of a structure with straw-covered floor and a temporary roof made of reeds, beneath the walls of a corner of the fortress, and just beyond where the participating animals has been penned. So as to give a flavour of how the town might have appeared in King Louis and Kenneth’s time, some of the photographs which I took during this festival, Le Rassemblement Medieval d’Aigues-Mortes,follow. After these, I will pick up my detective story again.

As my detective trail in ‘May we be Britons?’ has already showed, on board Hugh de Chatillon’s wondrous ship would have been Kenneth Macmathan, the eponymous, ancestral progenitor of the Mackenzies.

And as I then set out in ‘The Raven’s Skull’, the chronicler Jean de Joinville, in his ‘Life of Saint Louis’ gives a first-hand account of his own personal experiences on Louis’s Crusade, and seems to have had much to say about Hugh’s crusader nephew, Gautier de Chatillon, in particular. Joinville records that Gautier was often in his company. And, as I established, Kenneth must have been one of Gautier’s party.

In ‘The Raven’s Skull’, using Joinville’s narrative, I then went on to consider how Kenneth would have set out on Louis’s Crusade with Hugh, and then, following Hugh’s death in 1248, continued onwards with the crusaders so as to join King Louis; hence sailing to Cyprus, Egypt and Acre, with Louis, as a member of the company of Hugh’s nephew and successor, Gautier de Chatillon.

In our history of the Mackenzies, ‘May we be Britons?’, my brother Andrew and I also investigated another 13th-century family legend, that of ‘The Son of the Goat’, and this inexorably led to the conclusion, when coupled our other findings, from patronymics, seals in the Ragman Roll, heraldry, and other early evidence, that Kenneth was a member in the direct male line of the Scots royal house of Dunkeld. Hence, such a connection with prominent French noblemen like Hugh and his nephew Gautier is not a surprising one.

Now, the following further connections take us to what is now Syria, and to 10th-century Persia.

First, I have found evidence that Gautier’s party (hence with him Kenneth) must have comprised the party of knights which accompanied Joinville to Tripoli. This evidence, which I set out below, is reinforced by the fact that the then Count of Tripoli was Bohemond V of Antioch, who had been married to Alice of Champagne – an immediate descendant of King Stephen’s elder brother, Theobald. As such, the Count of Tripoli was a close cousin of both Gautier de Chatillon and Kenneth. (Both Gautier and Kenneth’s relationships to King Stephen are matters which we explored in the opening chapters of ‘May we be Britons?’)

Next, there is a crucial clue which I have spotted within the text of Sa’adi Shirazi’s ‘The Gulistan’ (‘The Rose Garden’).

Sa’adi’s work is collection of poems and stories, just as a rose-garden is a collection of flowers. Part autobiographical, it is widely quoted as a source of wisdom. According to Story 32 of Chapter 2, Sa’adi was captured by a troop of Crusaders whilst wandering in the desert not far from Jerusalem, during the period of his travels between 1226 and 1256:

‘Having become tired of my friends in Damascus, I went

into the desert of Jerusalem and associated with animals

until the time when I became a prisoner of the Franks, who

put me to work with infidels in digging the earth of a moat

in Tarapolis, when one of the chiefs of Aleppo, with whom

I had formerly been acquainted, recognized me and said:

“What state is this?” I recited:

“I fled from men to mountain and desert

Wishing to attend upon no one but God.

Imagine what my state at present is

When I must be satisfied in a stable of wretches.

The feet in chains with friends

Is better than to be with strangers in a garden.”

He took pity on my state and ransomed me for ten dinars

from the captivity of the Franks, taking me to Aleppo where he had a daughter and married me to her with a dowry of one hundred dinars.’

The only time window and place that fits for Sa’adi’s capture by Crusaders near Jerusalem in this period is aroundwhen King Louis IX and his Crusaders were in or near Acre, between 1250 and (which when they departed) 1254. And although Acre, Caesarea and Sidon are all possibilities, it seems to me that the most likely place of Sa’di’s capture is in the vicinity of Jaffa, this being by far the closest then port to Jerusalem – especially since the 13th-century French chronicler Jean de Joinville mentions an expedition there with King Louis, when they were in Acre.

To reinforce the evidence yet further, I have found that Joinville says that Louis sent Gautier (‘and my knights’) to Tortosa, and that he went via Tripoli, where he was entertained by the Prince of Tripoli. Tripoli (‘Tarapolis’) is whence, in ‘The Gulistan’, Sa’adi says he was taken by the Crusaders. Tarapolis is clearly not Tripoli in Libya, and Tortosa is self-evidently not the city of that name in Spain. Rather, Tortosa is the crusader city of that name within the County of Tripoli in the Lebanon – not far from the important fortress of Krak des Chevaliers – which must therefore be Joinville’s ‘Tarapolis’.

And the ‘moat’ in Tarapolis which Sa’adi says ‘the Franks’ put him to work digging must in turn be the excavations of the motte which had to be made in order to construct the outer walls at Krak des Chevaliers – these having specifically begun under King Louis, in 1250.

And I have found still more: in an ‘Epitaph’ to ‘The Life of St Louis’, Joinville actually mentions a trip which he says he made to Krak des Chevaliers in order to recover the shield of his uncle, Geoffrey V, who had died there in 1203.

Alice of Champagne was successively the Queen consort of Cyprus, regent of Cyprus, and of Jerusalem. She was the eldest daughter of Queen Isabella I of Jerusalem. In 1210, she had married her step-brother, King Hugh I of Cyprus, receiving the County of Jaffa as a dowry. It was her cousin, Hugh de Chatillon, Comte de Saint Pol, Gautier’s uncle, who, as I say, constructed a ship in Inverness, to transport his party of crusaders on King Louis’s crusade.

Now, where does Kish Island come into our story, and how does any of this connect with that?

The Island of Keish

The British orientalist, Sir William Ouseley (1767 – 1842), cites the mediaeval Persian story of Keish and his cat in his Travels, of 1819.

Ouseley relates, when speaking of the origin of the name of an island in the Persian Gulf, on the authority of a Persian manuscript, that in the 10th Century, one Keis, Keish, or Kish, the son of a poor widow of Siraf (at the time, a great trading port with India and the East, on the northern shore of the Persian Gulf), embarked for India, with his sole property – a cat:

‘There he fortunately arrived at a time when the palace was so infested by mice and rats, that they invaded the king’s food, and persons were employed to drive them from the royal banquet. Keis produced his cat, the noxious vermin soon disappeared, and magnificent rewards were bestowed on the adventurer of Siraf, who returned to that city, and afterwards, with his mother and brothers, settled in the island, which, from his, has been denominated Keis, or according to the Persian, Keish.’

The island of Kish, I have noticed (it was my finding this which set me on this particular trail of further research and detective work), appears within Sa’adi’s The Gulistan. At the beginning of Story 22:

‘I met a trader who possessed one hundred and fifty camel loads of merchandise with forty slaves and servants. One evening in the oasis of Kish he took me into his apartment and taking all night no rest kept up an incoherent gabble, saying … .’

So, it seems that Sa’adi actually visited Keish’s island.

What is more, as I mentioned in ‘The Raven’s Skull’, King Louis’s crusader base of Acre was plagued by rats at the time.

Hence, Keish was the prince in an earlier mediaeval Persian story of a cat with which he rid his king of a plague of rats, and it is a version of this, with Prince Keish replaced by Kenneth, who was the young heir to the chief at Eilean Donan Castle, which features in the Legend of the Birds – with Kenneth (who is exiled for a long period overseas for angering his father, travels afar and undergoes many adventures) ridding another king, who is evidently the French king, Louis IX, of a similar invasion of troublesome rats.

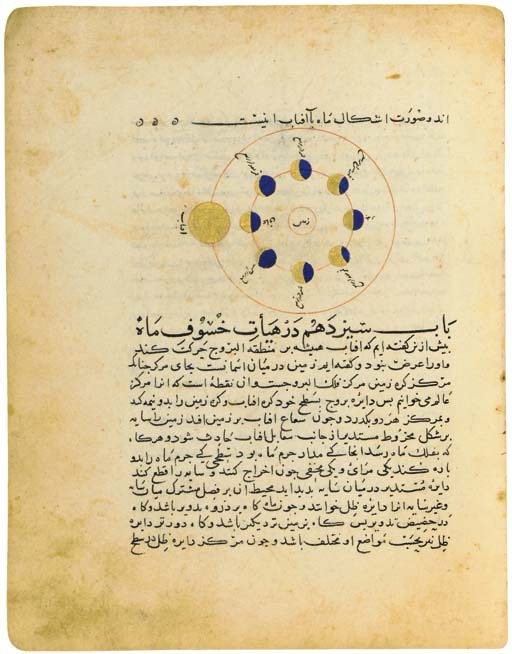

Sir William Ouseley states that the story of Keish and his cat appears in the ‘Tarikh-i-Wesuf’, which he gives as written by ‘Abdallah Shira’zi’. This 15th-century author, Abdallah ibn Faḍlallah Sharaf al-Din Shīrāzī, more commonly known as Wassaf or Vassaf, was a Persian historian of the Ilkhanate. Waṣṣāf, sometimes lengthened to Waṣṣāf al-Ḥaḍrat or Vassaf-e Hazrat, is a title meaning ‘court panegyrist’.

Amazingly – and this is a point which ties all of this together – both Sa’adi Shirazi and Wassaf were natives of the city of Shiraz (which was the capital of Persian Art, Culture and Literature, in the late 13th to early 14th Centuries). Sa’adi (1210 – 1291/2) spent his final years in Shiraz, and Wassaf (fl 1265–1328) was born there.

Not only this, but Sa’adi experienced the very same Mongol invasion as that which Wassaf was soon afterwards recounting by means of his very book that mentions the story of Prince Keish and his cat. For Sa’adi’s works ‘reflect upon the lives of ordinary Iranians suffering displacement, agony and conflict during the turbulent times of the Mongol invasion.’

Therefore, there is absolutely bound to have been contact and discussion between the younger Wassaf, the Persian historian, and his by now elderly compatriot, the poet Sa’adi, when they were together living in Shiraz.

A Copy of Wassaf’s Tarikh-i Wassaf, created in 17th-century Safavid Iran.

So, it seems highly likely that Kenneth Macmathan was one of the crusaders who, according to The Gulistan, captured the poet Sa’adi and held him as a slave, and that both Wassaf and Kenneth learnt the story of Keish and his cat from him.

And Kenneth must have then brought the story back with him to Eilean Donan Castle – where it later became jumbled in the oral tradition, progressively distorted as it was transmitted from person to person over the many ensuing centuries. (It is a common occurrence, I have found, for the transmission of oral tradition to become garbled in this way, but nevertheless to preserve a core of original facts, which serve as clues to the story’s ultimate derivation. The 13th Century, in particular, seems to have been a mine for such legends).

So, it is by this means – the transmission of the story of Keish and his cat from Sa’adi Shirazi to Kenneth Macmathan, with Sa’adi being a slave at the crusader fortress of Krak des Chevaliers, to Kenneth and his fellow knights in around 1250 – that the story must later have become merged into the history Eilean Donan Castle, so as to form a central part of its foundation legend. Hence, it is from all of this that the Legend of the Birds must surely have derived its source. This old story must have been told by the fireside within the ancient walls of Eilean Donan – transmitted, purely from memory, down some six centuries.

The story of Prince Keish is also the source of much of the legend of Dick Whittington and his cat, which bears many close similarities to the Legend of the Birds.

Since elements of the famous ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ are considered to have been a marriage of works by other, later poets, it also occurs to me that some elements of the Rubaiyat may well derive from lost works by Sa’adi, who was Omar Khayyam’s successor as a prominent Persian poet, and whose works would have flourished in Persia in the 15th Century. (Indeed, the collection that Edward Fitzgerald relied upon – the Bodleian Ouseley MS – in order to compose his ‘translation’ of the Rubayait camefrom 15th-century Shiraz, and it seems there is absolutely minimal evidence to suggest that the 12th-century Omar Khayyam wrote any poetry.)

The poet Sa’adi was to surface again in the western world, over 500 years later, when Sadi Carnot, the eminent French military engineer and physicist (sadly, later to die in relative obscurity at the age of 36, but now regarded as the founder of the Second Law of Thermodynamics), was named after him.

In his following particular poem, Sa’adi even mentions the metaphor of a bird which speaks the language of humanity. In Eilean Donan Castle’s foundation legend, Kenneth learns to speak the language of the birds, after he was given this supernatural power, when a child, by having drunk from a raven’s skull …

Since Sa’adi was recognised for the depth of his social and moral thoughts, and his poetry was deeply infused with peace-loving Sufi wisdom, we must bring into question the historical trope, as recounted in an Old Norse chronicle, which I quoted in ‘The Raven’s Skull’, whereby Kenneth and his followers are alleged to have committed the following atrocities in the Hebrides, when they went out to Sky [sic] in 1262/3:

‘They burned villages, and churches, and

they killed great numbers both of men and women. They affirmed that the Scotch had even taken the small children and raising them on the points of their spears shook them till they fell down to their

hands, when they threw them away lifeless on the ground.’

Or maybe Kenneth’s experiences whilst on Louis’s crusade had hardened him?

We shall most likely never know the answer to this. However, the encounter with Sa’adi and his stories must clearly impressed Kenneth and his successors at their chiefly seat of Eilean Donan Castle, and it is an astonishing cross-fertilisation of cultures which is preserved in the castle’s foundation legend, the Legend of the Birds.

We can safely also conclude that such oral traditions, usually dismissed as mere childish fairy tales, or total fabrication, are deserving of far closer examination and scrutiny than historians have tended hitherto to have given them.

Kevin McKenzie

Regent’s Park, August 2025

© Kevin McKenzie, 2025

(All images are in the public domain, or licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence)