Alchemy, Atheism and Attempted Assassination: what can we learn from the Mackenzies and the Radical Enlightenment?

After centuries of neglect, the 17th-century philosopher Spinoza was given new life by deep thinkers like Einstein. But only now in the 21st Century, with strong support from very recent developments in Neuroscience, is he beginning to be acclaimed as the neglected forerunner of the Radical Enlightenment – a movement far more fundamental to the development of modern scientific thought even than the mainstream thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. Misguided historians would have us believe that the Mackenzies were a backward, warlike coterie of Highland savages. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, they too were there at the very beginning of this brave new world begun by Spinoza.

Sir George Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Cromartie, is still something of an overlooked figure, not only in the context of the Union of Scotland and England, of which he was the chief architect, but also in the context of the Scientific Revolution. As many of you will already know, he was a friend of Robert Boyle and a patron of Isaac Newton, and in 1678 he is known to have had discussions with Boyle regarding instances of Second Sight which he had encountered in the Highlands.

What is less well-known is that, like Newton, Sir George had a passion for alchemy, which was at the time intrinsically bound up with their empirical research into the macroscopic and the microscopic – the laws of nature and the nature of matter. Newton’s alchemical manuscripts were destroyed in a fire, but we can still delve into this mysterious area, which gave rise to some of the greatest discoveries in the laws of physics, and some startling new connections emerge …

Whilst trying to find further evidence of the elusive relationship between George and Newton, I stumbled across a letter in 1675 recommending George’s philosophical qualifications to the Royal Society, and that presumably preceded an invitation for membership. The record of his admittance seems to be missing, but he was certainly a fellow by 1692.

I also found the following book in the catalogue of Newton’s library: “Several proposals conducting to a farther Union of Britian: and pointing at some advantages arising from it. [By George MacKenzie, 1st Earl of Cromarty.] 4o, London, 1711”. The fact that this book was published in 1711 suggests that the Earl’s friendship with Newton lasted several decades, and so the mutual interest in alchemy is interesting.

George owned a Ripley Scroll which, along with six alchemical manuscript volumes, he had inherited from his maternal grandfather, Sir George Erskine of Innerteil, who had himself been a prominent alchemist. Ripley Scrolls are mysterious documents whose meaning and symbolism are now largely lost. Many of the symbols are familiar alchemical ones: the hermetic vases, the toad, the dragon, the Bird of Hermes and the lions. In general, the toad often represents earthy matter, or “sophic sulphur” (sophic here implies that the grosser physical properties are absent); the Bird of Hermes is Mercury, and eating its wing has been interpreted as a stabilising act; the red lion is sulphur and the green lion mercury or vitriol or antimony. Mercury does not always represent quicksilver but may also refer to “sophicmercury”, or the philosopher’s stone. The sun represents gold, maleness or sophic sulphur; the moon, silver or sophicmercury; the dragon is a solar or phallic emblem; if winged it represents the volatile principle, and without wings the fixed principle.

The manuscript volumes contain material on Rosicrucianismas well as alchemical subjects copied from a wide range of authors. Poems by Ripley, and a version of the Hunting of the Green Lion by the Vicar of Walden are included: “Arbatel, or the magick of the auncient Philosophers the cheefstudie of wisdom. Anno Virginei partus saluberrimi 1602 Febii xiii.G.A. Norton’s Ordinall; Bloomfield’s Blossoms; The vicar of Walden, his hunting of the Green Lyon; Ane book named the Breviarie ofPhilosophie, be the unlettered Scholler, Tho. Charnock; John Bristoll his Alchymie.”

The “Vicar of Walden” appears to have been Andrew Abrahams, a vicar of Maldon in the reign of King Henry V, who also wrote a book called The Bird of Hermes. And a green lion consuming the sun is a common alchemical image, seen in texts such as the Rosarium philosophorum. The symbol is a metaphor for vitriol (the green lion) purifying matter (the sun), leaving behind gold. In alchemical and Hermetic traditions, suns can correspond to generative masculine principles, the divine spark in man and incorruptibility.

Perhaps, therefore, rather than a parliamentary statute, a judgment, or an architectural or garden plan, Sir George is holding a Ripley scroll in his portrait which hangs in the Great Hall at Castle Leod?

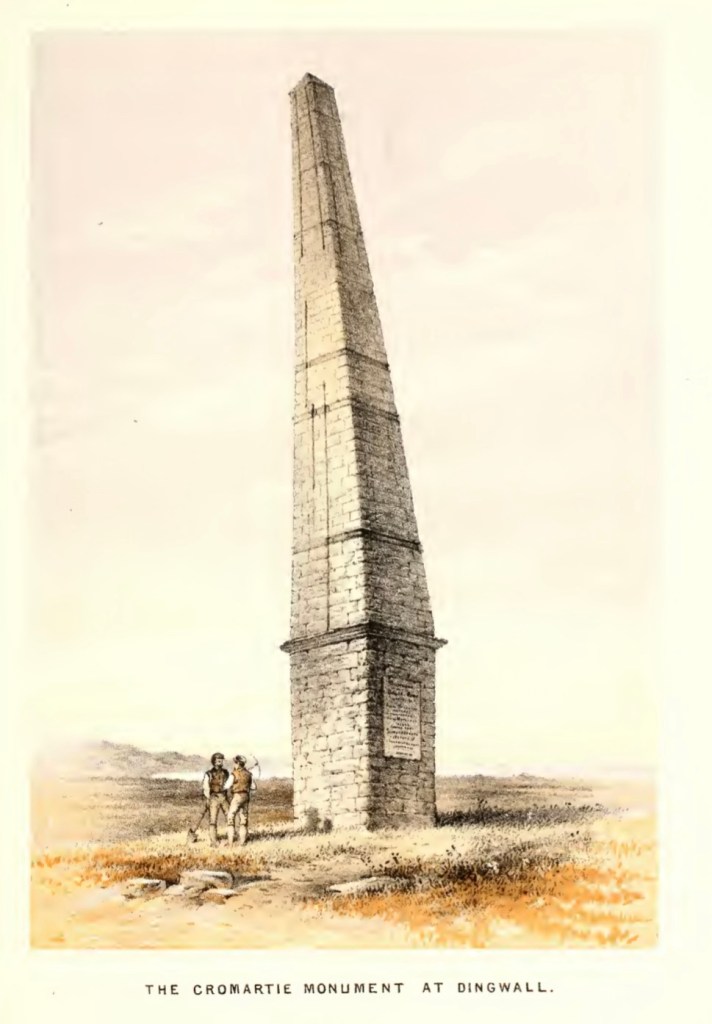

What it also intriguing is that George’s own crest was the sun in splendour, and that he left instructions to be buried near his father under an obelisk outside Dingwall Church.

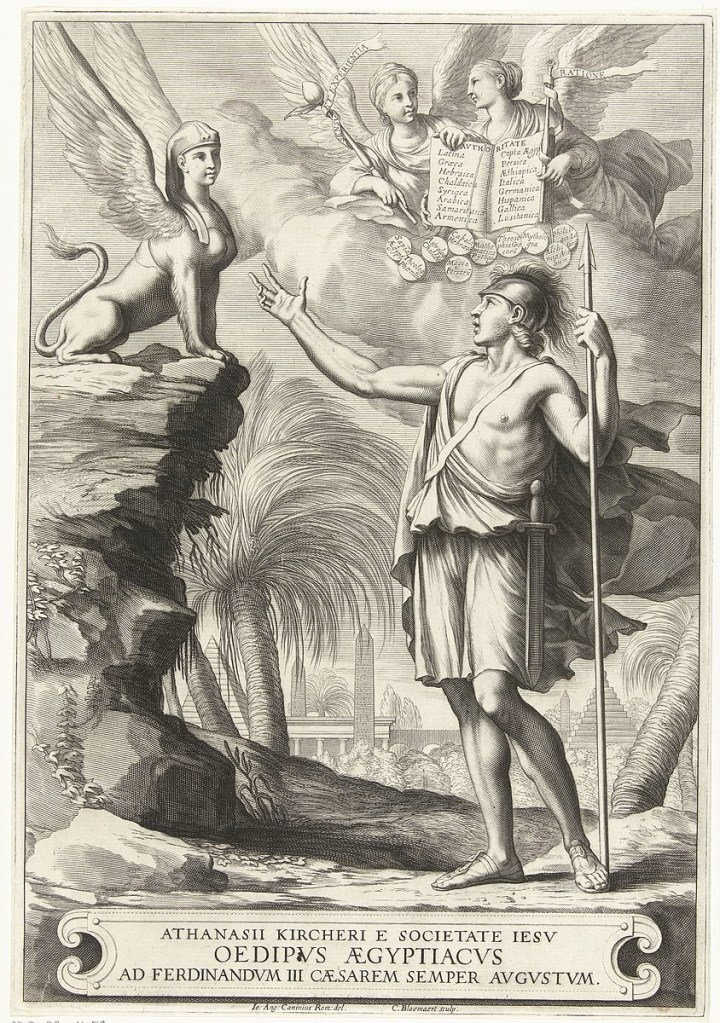

The choice of an obelisk brings to mind the work of the Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher, “the last man to know everything”. It is certain, given what we know of his library, his extensive reading, and the nature of his literary interests, that George would have read Kircher’s works.

“At the dawn of time, Kircher, explained, Adam, instructed by God and the angels, and guided by experience acquired during his centuries-spanning life, possessed perfect wisdom, which he passed on to his children. Noah and his sons preserved antediluvian knowledge from destruction by the Flood, which Kircher placed 1,656 years after the creation of the world and 2,394 years before the birth of Christ. But Noah’s son Ham polluted the Adamic wisdom with magic and superstition. Eventually the great Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistusrecovered the pure antediluvian wisdom and invented hieroglyphic writing to preserve it for posterity. But later Egyptian priests mixed the Hermetic wisdom with magic and superstition, creating, yet again, an ambiguous legacy, which was passed on to other nations.”

”Dobbs (1990) in a study of a Ripley scroll in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, emphasises the pervasive Christian symbolism in the scrolls, especially of death and resurrection. She comments on the obscurity of alchemical symbolism for the present day and suggests that rather than dismissing alchemy as irrational and incomprehensible, one may attempt to recover its meaning by historical methods, decoding it by analysis of premodern suppositions about life, death and resurrection. She makes a beginning in describing some of the imagery … but there is so much detail in the scrolls’ emblems that there is still a long way to go in explaining what lies behind them.”

The obelisk symbolised the sun god Ra, and during the religious reformation of Akhenaten it was said to have been a petrified ray of the Aten, the sun disk. It was also thought that the god existed within the structure.

George corresponded with his friend and political ally in the Scots Parliament, Murdo Mackenzie (successively Bishop of Moray and Orkney). Not only was the sun in splendour George’s crest, but in a letter to George’s first wife, Anna Sinclair, Murdo refers to him using a solar or planetary metaphor: “… Madame, if your Ladyship’s best conuienciecan allow me ane line anent my good Lord your husbandissoutherne good aspect under the superior orbes, and your hopfull familie’s weelfare (whoe are happy, as weell as honorable, in having youe for ther mother) it will werie much refresh me in this sequestrat corner of the world …”.

George’s theological views were clearly of a radical nature – verging on the atheistic or pagan – and it may be that, like others of a free-thinking philosophical persuasion, in a transitional age when Christian heterodoxy could still lead to severe penalties and social ostracism (his friend and patroness Queen Anne, whose chief Scottish minister he was, was very much an Anglican of the more bigoted end of the spectrum),he kept those views very much within his close-knit intellectual scientific circle and hid them from public view.

In September 1714, a letter sent from Edinburgh to the Earl of Mar in London begins:

“This place affords very little news … The Earl of Cromartie died Friday last, universally regrated. Upon hearing of the Queen’s death he shutt himself up in his closet for three hours, was very melancholy when he came out, went to bed and niver rose again.” The Earl had left instructions however – seemingly now less eccentric in the context of this article – to be buried outside the parish church of Dingwall (where, it seems, his father and grandfather had also been buried) under an obelisk on a large earth mound, a former place of assembly, which was perhaps originally the Viking “thing” (place of assembly) which forms part of the etymology of the place name Dingwall, and which was known from at least the 16th century as the moothill. The obelisk was built in 1710 but following an earthquake in 1816 it was dangerously leaning and so sadly had to be taken taken down in 1920. However, the late Earl Rorie’s mother, Countess Sibill, had a replica built in 1923. We cannot know what original inscriptions it may or may not have had on it, but some photographs which pre-date this do survive, and there are some more details preserved in the form of the 1923 memorial plaque, happily renewed in 1976 by the always wonderfully historically-conscious Rorie.

George’s death now brings me to another mysterious figure in the family. There is a Colin Mackenzie who wrote from Inverness offering his good wishes regarding the health of Anna Sinclair a few days before her death in October 1699. It has been suggested that this might have been Redcastle, but as we shall see from his mutual intellectual interests and the circles he moved in, Dr Colin Mackenzie, the eldest son of Daniel Mackenzie of Logie, makes far more sense as the likely author of this letter. He may also perhaps be the “Collin Mackenzie” who had been given two salt cellars, as appears an inventory of the silver which formed part of the contents of George’s apartments at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in about 1680, when James was in residence there as Duke of York and Scottish viceroy.

This Colin, who was a first cousin of the Mackenzie wife of my ancestor Bishop Murdo’s son, another Daniel, practised as a physician in Inverness, and may well have been one of George’s own personal family physicians.

From another George, the physician Dr George Mackenzie’s early 18th century family pedigree, we learn that Colin “was educated at the College of Aberdeen, whereafter he had learned his Philosophy. He applied himself to the study of Medicine, and having gone over to the Low Countries, he applied himself closly to his studies at the Universities of Lyden and Paris, under the then famous Professors of Medicine, and having received the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Rheims, he returned to his native country: but his immoral conduct, in the heat of his youth, obliged him to return again to his travels, and having staid for some time abroad, he returned again to his own county, where he practised medicine for many years with good success at Inverness and had a yearly pension settled on him, till his death, which happened in 1708.”

More than a decade ago, whilst helping my brother Andrew research his book (May we be Britons? (published in 2012)), on the history of the Mackenzies, I stumbled across a letter which forms part of the extensive, wonderfully preserved archive of Mackenzie family correspondence, the Delvinepapers, held by the National Library of Scotland. Dating from the 1690s, in this letter Colin mentions the famous Dutch philosopher, Spinoza.

Spinoza, like Cromartie and Newton, was especially concerned to understand, in his case by the alternative method of using pure reason, the nature of matter. He famously equated God with Nature and saw mind and body as one substance with God. And just as Colin was disinherited by his father for his “extravagant” theological views, Spinoza, by a cherem, or writ of excommunication, in July 1656, was famously cursed and banished from Amsterdam’s Sephardi Jewish community. They were both very courageousindividuals who risked much in their personal lives by bravely standing up for and not compromising their intellectual beliefs.

The debate continues as to whether Spinoza should be regarded as an atheist or a deist, and his views were so radical that his works were banned from the tolerant free-thinking Netherlands. After the posthumous publication of his ground-breaking Ethics on his death in 1677, even his supporters could only propagate his works by hiding behind condemnation. This condemnation continued even until well after the time of Voltaire, who, normally so inspiring, wrote a smug and sneering, blatantly anti-Semitic verse about the philosopher.

My detective work shows that Colin ended his Latin studies at Aberdeen University in 1656. (In the University’s records, there is a “Colinus Mackenzie, minor de Loggie Rossensis” 1652-56). Since he then went on to Leiden, where we learn from Dr George’s history that he applied himself “closely” in his studies and graduated with an MA in 1661, we know that he studied a 5-year course in Natural Philosophy, as a precursor to his further studies in Paris and the doctorate in medicine with which he graduated from Rheims. He must therefore have begun his course at Leiden in 1656, immediately after he left Aberdeen. He would thus have been at Leiden University in the very same years and faculty as Spinoza, because we can establish that Spinoza had gone to Leiden to study a course in Natural Philosophy, so as to learn about the latest developments in Cartesianism, and that he had returned from Leiden to Amsterdam by late 1658 or early 1659. Spinoza’s library included books on anatomy and so he and Colin were most probably in the very same class together. And there is also strong evidence to suggest they would have been friends, or at the very least close associates. In particular Spinoza’s close friend and protector, Pieter (or Petrus) Serrarius, who was Spinoza’s main contact with the outside world, was for a while a member of the spiritual community of the French-Flemish mystic Antoinette Bourignon, who taught that the end times would come soon and that the Last Judgment would then be felled. Her belief was that she was chosen by God to restore true Christianity on earth. Serrarius even write a book about her and we learn that Colin also became a follower of hers.

As we have seen of Colin from Dr George’s history: “… but his immoral conduct, in the heat of his youth, obliged him to return again to his travels.” It would in fact seem that, far from being the solitary recluse as which he has often been portrayed, Spinoza and his circle enjoyed an active, fun-loving social life at this time. It is frustrating that his correspondence only survives from 1661 onwards. However, we know that in nearby “sleepy Rijnsburg”, to which the philosopher had moved by the Summer of 1661 (which would have been the last year of Colin’s time in Holland), he often visited nearby cities to meet with his friends there. It is likely that a circle of them developed in Leiden, to hear and discuss what he had to say on philosophical matters. “Spinoza’s conversation had such an air of geniality and his comparisons were so just that he made everybody fall in unconsciously with his views … one always found him in an even and agreeable humor … He had a wit so well seasoned that the most gentle and the most severe found very peculiar charm in it.” Though his furniture and clothes were “sober and humble”, he is recorded as being a “tidy dresser” – something which also emerges from the Delvine papers as regards Colin and his siblings, where we learn of them buying Spanish lace cravats and “champagne” wigs for one another in Brussels; and Spinoza later wrote something which must surely have come from personal experience during his youth: “As far as sensual pleasure is concerned, the mind gets so caught up in it … that it is quite prevented from thinking of anything else. But after the enjoyment of sensual pleasure is past, the great sadness follows …”. Later in life, however, for his diversion,the philosopher liked to collect spiders, throw flies in their webs and watch them fight each other, so as to create “battles”, which caused him great amusement.

Dr George goes on to say regarding Colin: “This learned gentleman died unmarried, altho he was a great admirer of the Fair Sex, and was so successively fond of one of them, that he made choice of her for his spiritual guide, in his old age, I mean the famous Antonia Bourignion [sic] … And after her death her writings made a great many proselytes in Britain, who are always fond of new Revolutions, & especially in Scotland, where a great many of our gravest and most learned Devines and Philosophers became her admirers, and among them there was none that had a greater veneration for her than this gentleman, whom I have often heard say with great warmth, that he as firmly believed her to be inspired and sent from God, as either the Apostles or Prophets were. But such as went to be particularly informed of this lady’s visions and revealing.”

It was surely therefore Pieter Serrarius who must have introduced Colin to this mystic. Pieter too was of Scottish extraction and a member like Cromartie’s friend Robert Boyle of the circle of another polymath, Samuel Hartlib, “the Great Intelligencer of Europe”. Hartlib set out with the universalistgoal “to record all human knowledge and to make it universally available for the education of all mankind”. His work has been compared to modern internet search engines. Most of Spinoza’s most intimate friendships began during the mid to late 1650s and he may well have attended meetings of these liberal, tolerant, and generally anti-clerical religious free-thinking interpreters of Scriptures, known as Collegiants, who included dissenters of all types, and whose views on religion and morality had much in common with his own.

Pieter Serrarius was also part of a community that attended readings of the Old Testament in Spinoza’s synagogue in Amsterdam. It was he who looked after Spinoza at the time of his banishment in 1656, who welcomed him into a new life as part of the small community of fellow “millenarian” lapsed Calvinist and Quaker Collegiants in Rijnsburg near Leiden, of which Colin was part, and in Spinoza’s lifetime he was the carrier of Spinoza’s correspondence to Henry Oldenburg, the Secretary of the Royal Society. Oldenburg, via their mutual friend the astronomer and telescope maker James Gregory, was also a correspondent of Cromartie. In fact a perusal of Spinoza’s correspondence with Oldenburg shows that the only people whom the two of them were copying in were Robert Boyle, who was very receptive – they were passing regards to each other via Serrarius and Oldenburg – and Sir Robert Moray who was also interested. Spinoza and Boyle corresponded with another regarding Boyle’s Essay on Niter, debating by letter the philosophical implications, in support of the concept of the homogeneity of substance, by means of experiments on saltpetre, or potassium nitrate.

In a time of pandemic, as we are now in ourselves, we must not forget that this was also a time of plague, and sometime between 1665 and 1669, Henry Oldenburg wrote to Spinoza:

“Kircher’s Subterranean World has not yet appeared in our English world, because of the plague, which prohibits almost all commerce. In addition we have this dreadful War, which brings with it nothing but an Iliad of evils, and almost banishes all civilized behavior from the world.”

That same book by Kircher was also one of the topics which Christiaan Huygens and Spinoza discussed; given Cromartie’s associations with the sun symbol, it is interesting to note that Antoinette Bourignon believed herself to be the “woman clothed with the sun” in The Book of Revelation; and this group also seems to have interested itself in prophecy – which of course overlaps with George and Second Sight.

A fallen obelisk later appears in a portrait which would have been commissioned by Dr James Mackenzie, another member of Bishop Murdo’s family line, who was the son of Colin’s cousin Isobel, who followed him to Leiden and went on to have even more successful career in medicine. The portrait is of the young Sir Lister Holte and his brother Charles, who were Dr James’s protégés as nephews of his wife Elizabeth, the mistress of Aston Hall in Warwickshire, and it still hangs over a fireplace there. It was this specific connection which brought my own branch of this family line down from Inverness to England. Dr James was also tutor to Cromartie’s grandchildren. And here we have an intriguing link between Spinoza and the philosopher David Hume. For Hume was a friend and associate of Dr James.

In the second part of this article I shall go on to explore several more figures in the family and their associations with this radical, free-thinking circle. And I will mention some fascinating, as yet unpublished, detective work which I undertook in relation to a mysterious, previously unidentifiedportrait, so as, in more ways than one, to complete the picture.

PART 2

In Part 1 of this article we looked at Sir George Mackenzie, 1stEarl of Cromartie’s connections with early science and alchemy, and also how the long neglected but increasingly now highly regarded radical, free-thinking 17th-century philosopher Spinoza appears to have been a friend or close associate of Dr Colin Mackenzie.

Spinoza’s long-term acquaintance, the astronomer, Christiaan Huygens, famously discovered Saturn’s rings. The philosopher supplied lenses to him for his telescopes, and he too was part of Cromartie’s literary and scientific, Royal Society circle. Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh corresponded with Christiaan Huygens and his verse Caelia’s Country House and Closet there were affinities between the house and garden there and Huygens’s house, Hofwijck – which Spinoza must have visited during the time when he was living as a neighbour in Voorburg.

Spinoza’s lens-grinding technique and instruments were so esteemed that Christiaan’s brother Constantijn Huygens ground a “clear and bright” 42 ft. telescope lens in 1687 from one of Spinoza’s grinding dishes, ten years after his death. Constantijn later mentions a meeting with Rosehaugh (“a clever man”) at Court (most probably Kensington Palace, as King William seems to have been there during the first week or so of January 1689/1690) and a planned trip to Holland (where his nephew Simon was at university at the time),which in the event never materialised, because of Rosehaugh’s death in 1691.

Like Sir Robert Moray (a close friend of Cromartie, with whom he escaped to the western isles as a fellow royalist shortly after the execution of King Charles I), Rosehaughhoped that the New Philosophy could overcome religious fanaticism, and he published Religio Stoici: the Virtuoso or Stoick, with a Friendly Address to the Fanatics of all Sects and Sorts (1663). It is often forgotten that his harsh treatment of the Covenanters which earned him the epithet as Lord Advocate of “Bluidy Mackenzie” was very much part of a desire for peace and hatred of the fanaticism which had caused the far bigger evil of the Civil War. As with Spinoza, an admiration for the Greek and Roman Stoics and a strong free-thinking anti-clericalism/sectarianism, not bound by religious dogma, permeates Rosehaugh’s philosophy.

Another strong supporter of this campaign for religious toleration and political moderation, which was actively pursued by Rosehaugh’s patron and political ally, King James II and VII, to whom he was Lord Advocate, was Sir Robert Sibbald, James’s royal geographer, who had earlier been a protege of Moray. Sibbald had visited Spinoza’s synagogue in Amsterdam and Roman Catholic chapels in Paris, experiences that “disposed me to affect charity for all good men of any persuasion.” Sibbald collected rare works on Cabalism, Lullism, Hermeticism, and Rosicrucianism, and his occultist library became a valuable resource for students of “speculative Freemasonry.” He was a correspondent of my ancestor Murdo Mackenzie when he was Bishop of Orkney: Murdo, whose son Alexander was knighted by James and who was a cousin, friend and political ally in the Scots Parliament of both Cromartie and Rosehaugh, supplied material for Sibbald’s geography of the islands. Murdo in his long life (he died in 1688 approaching it is said nearly 100, and his death was much lamented by all who knew him) was like his teachers, “the Aberdeen doctors”, notably conciliatory in his approach to religious dogma: with his shifts and turns, to manoeuvre his way and survive as harmlessly and benevolently as possible through the religious and political upheavals of the 17th century, he can be compared to the Vicar of Bray. So he too was very much part of this same, free-thinking intellectual circle.

I can bring us a little closer to visualising one member, at least, of this little world in the mid-1650s, which was the rootof so much that we take today for granted. For my researchinto the above portrait, relying on both my forensic analysis of the details which appear and contemporary accounts of the following incident, I believe, shows beyond reasonable doubt that it is a portrait of our brave young philosopher, Spinoza, as he would have appeared at this very time.

Reports exist of Spinoza being punched, payments failing to be collected for his business (which he was running for his father), and his hat being trampled on and damaged. In May 1655 he had one of his endlessly procrastinating creditors, Anthony Alvarez, a jewel dealer, arrested and taken to an inn, the De Vries Hollanders (The Four Dutchmen), and held until he paid him the full amount owed. First Alvarez hit him on the head with his fist but they later came to an arrangement which included Spinoza paying for the costs of his arrest. However, when Spinoza then returned with the money for this, Anthony’s brother Gabriel was waiting for him in front of the inn “and hit the plaintiff on the head with his fist without any cause, so that his hat fell off; and the said Gabriel Alvarez took he requisitionist’s hat and threw it in the gutter and stepped on it.”

In July of the next year, for his heretical views, the Beth Dinexcommunicated Spinoza from the Jewish community of Amsterdam with an unusually vehement and furious cherem, involving extreme prejudice, ostracism, and curses which echoed the famous phrases from Deuteronomy 4:7. No Jew was permitted to communicate with him in any way or accord him favours, nor be under the same roof; none should stay with him or be within four cubits [two metres] of his vicinity(given the social-distancing rules, again an uncanny parallel with the current pandemic), nor read any paper composed or written by him. It is recorded that he kept and continued to wear as a souvenir the coat which he was wearing shortly before his excommunication, when an attempt was made to assassinate him in the street: “Mr. Bayle writes, too, that on a certain occasion, when Spinoza was coming out of the theater, he was attacked by a Jew, who gave him a slight cut on his face with a knife, and that he suspected that it was an attempt on his life. However, Spinoza’s landlord and his wife, both still alive, tell me that he had often told them about this in a different way, namely, that on a certain evening when he was coming out of the old Portuguese synagogue he was assaulted with a dagger, seeing which, he turned around, and thus the thrust was received by his clothing, of which he still kept a garment, as a lasting reminder.”

As appears never previously to have been spotted before I myself did so, the sitter in the portrait is wearing both a damaged hat (it contains a distinct triangular nick in the brim) and a torn coat: there is what appears to be a small vertical slash in the exact place where Spinoza would have been stabbed in the chest with a dagger during an assassination attempt which occurred. For if you were trying to kill someone you would aim your dagger at their heart. That is of course slightly on the left side of one’s chest. Let’s assume the assailant was right-handed (the most likely, statistically). If as they were doing this Spinoza “turned around” to avoid the knife – as he says he did – and if, say, this was anti-clockwise and he moved slightly back – which would be the instinctive reaction – the dagger (as we know it did) would not only go into the coat but at a point level with one’s heart and on the right-hand side, instead of the left. That’s exactly where the tear appears. If he had turned clockwise that’s a less likely scenario as he would then have been turning his left shoulder into the thrust of the dagger, even if at the same time he were stepping back. That wouldn’t be an instinctive thing to do at all.

Rembrandt had connections via the Huygens family and his house in Amsterdam was in the Jewish Quarter, just a few streets away from Spinoza’s family home, which fronted the Houtgracht. In fact, Rembrandt, in the 1630s, had lived on and off in the home of his agent, Hendrik Uylenbergh, a well-known art-dealer, which was located in the Breestraatdiagonally opposite, and in 1639, after marrying Uylenbergh’sniece Saskia, bought the house next door. And it is recorded that one of the students in Rembrandt’s workshop, LeendertVan Beyeren, lodged in the home of Spinoza’s Latin tutor, until his death in 1649. (This man was Franciscus Van Enden, whose mother was a Barbara Janssens. My maternal grandmother’s Franco-Dutch Huguenot ancestral line wasliving at the time in Leiden. Amongst them however were Daniel Ver Veelen, son of a Catharina Janssens, who was living in Amsterdam, “by the Golden Spoon” on the nearby Singel canal, and Abraham and Jacob Boots, both art collectors. It is likely that Daniel, and/or his wife Anna, was a schoolteacher at Van Enden’s school, where Spinoza later studied).

In his known, later, portraits, Spinoza appears clean-shaven. However, as we know from Rembrandt’s drawings, beards were traditionally worn by members of the Jewish community in Amsterdam as a sign of their faith. Spinoza must therefore have shaved off his beard as a symbol of his distancing himself from them some time in the aftermath of his excommunication, and the apparent facial structure, featuresand age of the sitter – he would most probably have been aged 23 in July 1656 (and the most recent suggested date for the portrait is 1655 to 1657) – all fit perfectly with the sitter in the portrait. And we learn from Brother Tomas and Captain Matranilla, both writing in 1659, that the young man was good-looking and of an unmistakeably Mediterranean appearance: “a small man, with a beautiful face, pale complexion [“bianco”], black hair and black eyes” … “ a well-formed body, thin … a beautiful face” … “an olive-colored complexion, with something Spanish in his face” … “his skin was quite black [swart], his hair black and curled, and his eyebrows were long and black.”

When all of this is put together, there are far too many coincidences. So this is surely a portrait of the young philosopher, showing exactly how he would have appeared around the time when he was a friend or close acquaintance of Dr Colin Mackenzie at Leiden.

What is significant about all of this is that we can now place the Mackenzies not only as part of the genesis, as we already know (my brother Andrew covered this in depth in his history) of the Scottish Enlightenment, but also of the much more rarefied circle of Spinoza and the Radical Enlightenment. It is now even believed that Spinoza’s philosophy grew out of and took shape not so much under the influence of his tutor Van Enden, but rather under that of his close friend Serrarius, whose anti-clerical ideas and disdain for organised religion emerged in new form, with stunning philosophical clarity and precision, in the Ethics and Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. So dangerously radical and atheistic a thinker was Spinoza that his views were considered anathema for the best part of a hundred years after his death, and his views could only be disseminated by admirers in covert fashion. For instance, whilst Denis Diderot lavished five times more space on Spinoza in his Encyclopédie (a complete original set of first editions of which I was lucky enough to see a year or two ago, at the Chateau de Menthon on Lake Annecy) than on Locke, he was forced to criticise him, and similarly Montesquieu, whose philosophy was Spinozist through and through, was forced, so as to avoid persecution by the church, to deny him and make a public declaration of his faith in a Christian Creator God.

So the reference by Colin to Spinoza in his letter to Mackenzie of Delvine is a rare find indeed.

Even now, in a world of endemic political and religious bigotry, populism and sectarian division, there is much still to be learned from the bravery of this civilised group of original free- and forward-thinking individuals – prepared both to stand up for tolerance and decency and to avoid the cowardice of following the herd or reducing themselves to the lowest common denominator. As C S Peirce wrote in Spinoza’s Ethic (1894):

“Spinoza’s ideas are eminently ideas to affect human conduct. If, in accordance with the recommendation of Jesus, we are to judge of ethical doctrines and of philosophy in general by its practical fruits, we cannot but consider Spinoza as a very weighty authority; for probably no writer of modern times has so much determined men towards an elevated mode of life. Although his doctrine contains many things which are unchristian, yet they are unchristian rather intellectually than practically. In part, at least, Spinozism is, after all, a special development of Christianity, and the practical upshot of it is decidedly more Christian than that of any current system of theology.”

Article written by Kevin McKenzie